Scientists from Lomonosov Moscow University, Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEE RAS) and Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences studied the acoustic structure of alarm calls in a highly social rodent species, the Harting's vole (Microtus hartingi). The phenomenon of collective explosive emission of alarm calls by several animals that strictly synchronized their calls was discovered and described in detail. Surprisingly, the synchronization of alarm calls was observed not only within groups, but even between neighboring groups of voles.

The alarm calls of the Harting's vole remained a mystery for a long time. There was only one article in the literature that described 1 (one!) alarm call, accidentally recorded on a bat detector by a Bulgarian scientist (Pandourski, 2011). This call was surprisingly high-frequency, above 17 kHz, more than twice as high as the alarm calls of other vole species. Although laboratory colonies of Harting's voles have lived happily in captivity for about 20 years, no one has ever heard or recorded alarm calls from them. Therefore, there was a reasonable doubt that the call described did not belong to Harting's vole, but to someone else.

In the course of studying the vocal range of the Harting's vole, scientists tried their best to get alarm cries from the animals or to make sure that they are not produced. However, it is not so easy to scare laboratory rodents that grew up in cages and are accustomed to the regular presence of people. Temporary deprivation of shelters, unexpected hand waves, imitation of an aerial predator flying over the cage - nothing helped. Then it was decided to plant groups of voles, consisting of a pair of founders and their cubs aged 2-3 months, in outdoor mesh enclosures. Which would not allow the voles to run away and at the same time protect them from predators. And provide natural predators with access to these enclosures. And provide the voles with a thick layer of sawdust and hay in which they could dig holes.

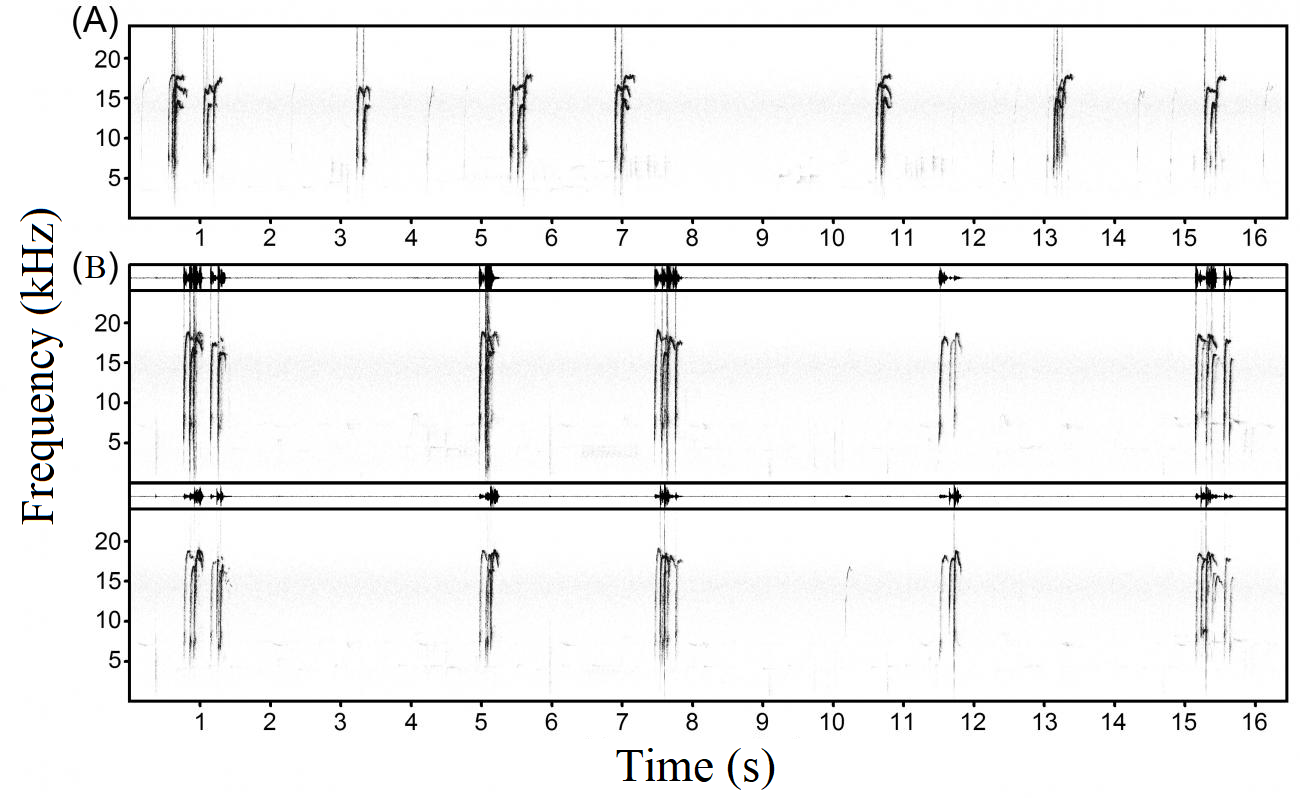

Since humans did not frighten the voles, but scared off potential predators, the cries had to be recorded "blindly". An automatic recorder was used, equipped with two microphones directed at an angle of 180 degrees to each other and simultaneously recording two adjacent groups of voles. Since the recording was done in stereo mode, it was possible to distinguish which group of animals was screaming at a given time by the relative intensity of the signals on the right and left tracks. The stimuli that caused alarm cries in the voles were natural predators that sat on the roofs of the enclosures: magpies, crows, owls, ferrets, feral cats, weasels. Although the predators could not harm the voles in any way, their immediate proximity frightened the voles, causing them to flee into a hole and produce alarm cries. Sometimes the cries of predators along with blows on the net were also recorded. In total, several thousand alarm calls were recorded from ten different family groups, each containing between 4 and 15 voles.

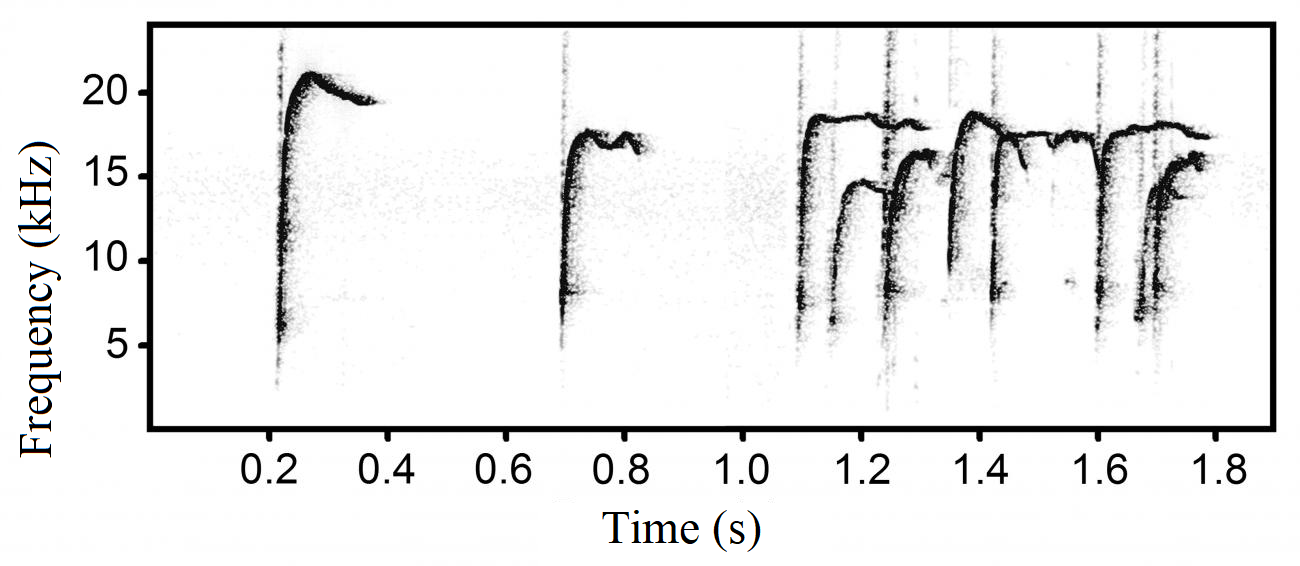

Firstly, it turned out that Harting's voles do produce alarm calls, in the form of long series with intervals of several seconds between calls. And these calls are high frequency, on average up to 17 kHz, and the highest up to 22 kHz. Moreover, the main part of the call is located just in the high-frequency region, above 12 kHz, and adults practically do not hear this frequency. Therefore, from the entire sound, people hear only a very short ascending whistle, similar to a bird's. Therefore, it is not surprising that there was no evidence of alarm calls of this species in nature, people simply did not hear them.

Secondly, it turned out that Harting's voles often emit alarm cries simultaneously as a group. Moreover, they somehow manage to start screaming before the scream of another animal ends. As a result, the screams are emitted in "bursts" in each of which the screams of several animals are mixed and which are separated by long intervals. Moreover, not only voles of one group can synchronize their screams, but also two neighboring ones, which could hear but could not see each other. This indirectly confirmed that the voles began to scream immediately after receiving an auditory stimulus.

So far, this is the only species of mammals for which the phenomenon of complete synchronization between animals when emitting alarm cries at a predator has been discovered. The adaptive biological significance of emitting collective synchronized alarm cries is still unknown. Perhaps this makes the screams more noticeable to members of the family group, perhaps simultaneous screaming allows disorienting the predator, perhaps the number of simultaneously screaming individuals can indicate the degree of threat. But all these assumptions require further study and can be tested not in captivity, but in natural populations of Harting's vole.

The results of the study were published in the journal Behaviour: Volodin I.A., Rutovskaya M.V., Golenishchev F.N., Volodina E.V., 2024. Startle together, shout in chorus: collective bursts of alarm calls in a social rodent, the Harting’s vole (Microtus hartingi). Behaviour, v. 161, N 8-9, p. 587-611.