Researchers from Lomonosov Moscow State University and the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences studied the use of rutting calls by male Siberian maral Cervus canadensis sibiricus as indicators of individuality and competitive advantages of males fighting for harems of females with rival males. During the rutting season, male deer scream a lot. They use these screams to attract females and to scare off other males - potential competitors. What features of the screams carry information about the quality, size and age of the male? This is known for European subspecies of red deer. Females choose males with low formant frequencies in the scream; such screams sound more bassy to the ear. However, the screams of the Siberian maral are very high-pitched, and low formants cannot be manifested in them. Scientists had to find out what acoustic features encode the status of males and how they are related to the individual characteristics of the maral's rutting screams.

Observations and sound recordings were conducted at the Kostroma Reindeer Husbandry Center (http://kostroma-hunter.ru/), an antler farm that breeds marals brought from three reindeer farms in Altai. The Center’s 70-hectare enclosure housed a herd of 22 adult males (aged 5-10 years), 34 adult females (aged 2-10 years), 20 young males (aged 2-4 years), and 18 young marals under one year old. The enclosure marals are wary of humans, but not afraid of them or aggressive towards them, which allowed us to approach the animals at a distance of 30-40 m during data collection. All adult animals were individually tagged with ear tags. The marals were free to roam throughout the enclosure; females could move from one harem to another at will.

Fourteen adult males were making rutting calls and trying to win their own harems. A male was considered to be in a harem if he managed to maintain a harem of five or more females for at least two days. During the 15 days of observations covering the period of peak rutting activity, there was only one harem in the enclosure for three days, two harems for nine days, three harems for two days, and four harems for one day. Six harem males maintained a harem for an average of 5.2 days and never became a harem male again after losing it.

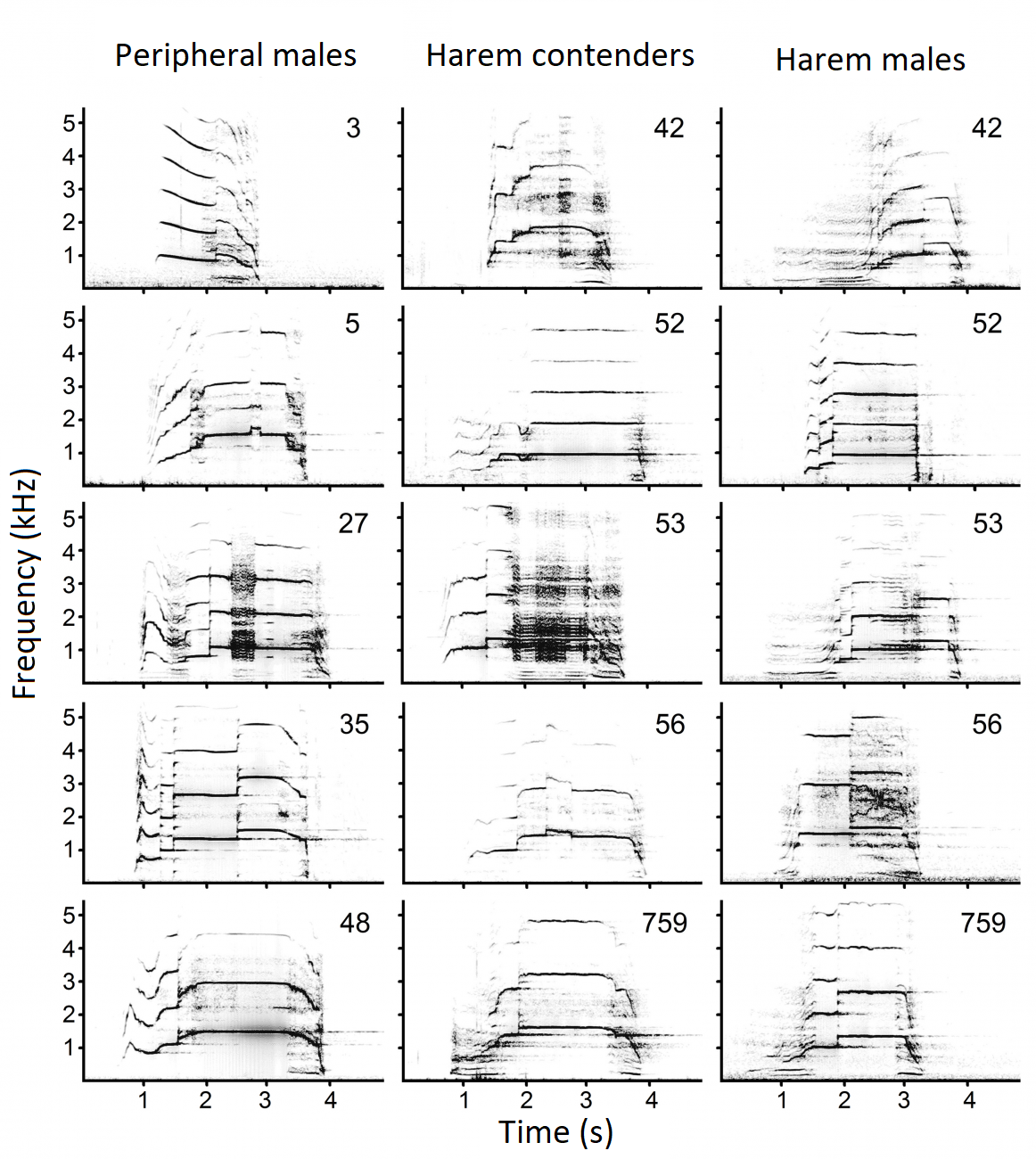

In the acoustic structure of male rutting calls, both features of the harem status of the male and features associated with his individuality were found. Compared to peripheral males that also emitted rutting calls but failed to win the harem, the calls of harem males were shorter and higher in terms of the minimum fundamental frequency (one of the features determining the general contour of the call). After winning the harem and changing the status from a harem contender to a harem male, each male shortened his own calls, decreased their initial and maximum fundamental frequency, and increased the minimum fundamental frequency. Evaluation of the acoustic parameters using multivariate statistics methods showed that for 78.9% of calls, the male status was determined correctly based on the call structure. This value was significantly higher than the random level. Thus, rutting calls reliably encode the status of a male as a harem one, a contender for a harem, or a peripheral one who will not be able to win a harem this season.

Individuality features in male calls were much weaker than status features. Only 53.2% of calls were correctly assigned to the males that produced them. This finding is consistent with long-term data on the analysis of the acoustic structure and censuses of male European red deer based on their voice (the so-called "roar" censuses). Long-term data show that such censuses are unreliable and do not reflect the real number of males in the census sites. Although the calls of European red deer and Siberian marals are individualized, they cannot serve as a vocal "signature" (the so-called vocal signature) for each specific male due to their high intra-individual variability. However, these calls reliably mark the status of males as harem holders. The study also showed that status and individuality features in male calls are encoded by different acoustic parameters.

The results of the study were published in Q1 of the Journal of Zoology (London): Sibiryakova O.V., Volodin I.A., Volodina E.V., 2024. Rutting calls of harem-holders, harem-candidates and peripheral male Siberian wapiti Cervus canadensis sibiricus: Acoustic correlates of stag quality and individual identity. Journal of Zoology.