At the end of March, paleontologists from Belgium, Great Britain and Russia published a detailed description of the Early Cretaceous pliosaur Luskhan itilensis. This taxon was named back in 2017, but then a short report was made in Current Biology to speed up the publication of the find. The detailed description was now published in the British Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

The remains of a pliosaur were discovered in 2002 on the banks of the Volga near the Slantsev mine (Ulyanovsk region) in the deposits of the Hauterivian stage of the Cretaceous period (about 130 million years old). It was possible to extract an almost complete skeleton of the animal from the enclosing clays. Painstaking work on the preparation and conservation of fossil remains continued for more than 10 years. And it’s not surprising - the skeleton reaches 6.5 m in length (the length of the skull alone is 1.6 m).

The name Luskhan itilensis given to the pliosaur is based on Mongolian mythology and is associated with Lus, the master spirits of reservoirs, and their ruler Luskhan. Itil is the ancient Turkic-Mongolian name for the Volga. In general, the name of the fossil reptile can be interpreted as “lord of the Volga waters.”

For a long time, almost nothing was known about Early Cretaceous pliosaurs; researchers called this period the “Early Cretaceous gap” in the history of pliosaurs. However, discoveries in recent years have made it possible to fill this gap.

Luskhan's anatomy is unique among pliosaurs. Previously, paleontologists believed that all representatives of pliosaurs (both Jurassic and Cretaceous) were ferocious predators that hunted large prey. However, a study of the remains of Luskhan showed that its skull was similar in structure to representatives of another, unrelated group of short-necked plesiosaurs from the family Polycotylidae, which were small and fast fish-eating forms. Such convergent similarity with polycotylides demonstrates the unexpected ecomorphological diversity of pliosaurs and the more complex nature of their evolutionary history than previously thought, and also refutes the prevailing stereotype that all pliosaurs without exception belong to superpredators.

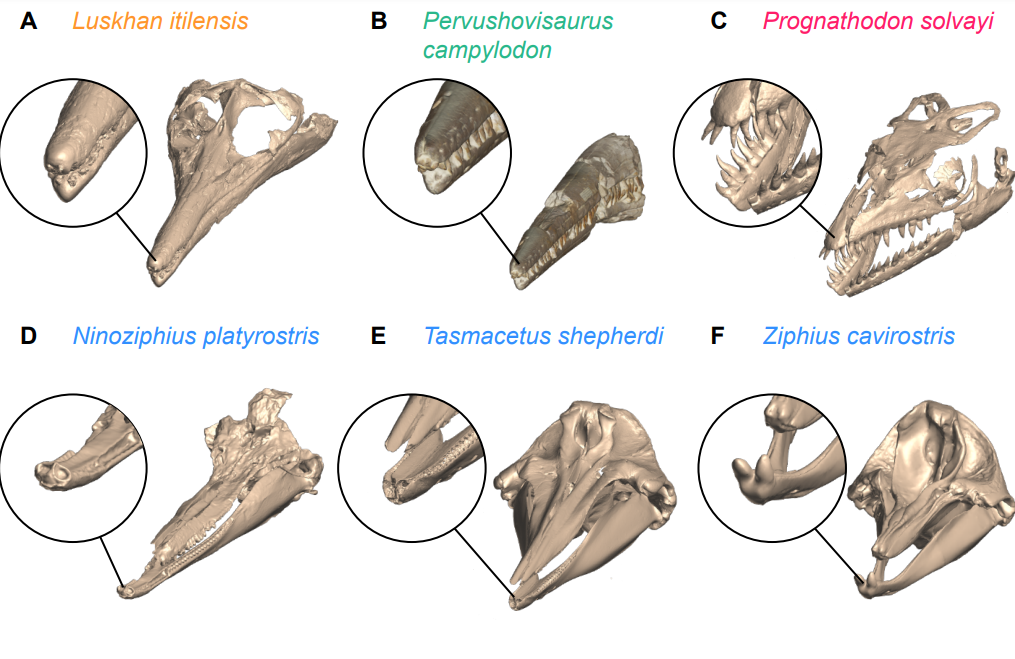

One of the striking anatomical features of Luskhan is the forward-directed first pair of teeth of the upper jaw. Similar forward-protruding teeth at the tip of the upper or lower jaw are found in some ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, and a number of fossil and modern cetaceans. Thus, in some beaked whales (for example, Ziphius cavirostris), such protruding teeth are used during mating tournaments between males. Whether such complex behavior could also be characteristic of pliosaurs is a question that cannot yet be answered.

In addition to the scientific examination of the bones, the authors of the work also created a complete three-dimensional reconstruction of this animal. Employee of the Institute of Economics and Economics of the Russian Academy of Sciences N.E. Prilepskaya, using a high-precision metrological 3D scanner Artec Space Spider, scanned all the bones of the Luskhan skeleton, and then assembled their three-dimensional models, which were posted as an appendix to the article. Based on 3D models of bones, the famous Russian paleosculptor Vlad Konstantinov, who previously worked in the popular science paleontological projects of National Geographic, completely reconstructed the skeleton of Luskhan, virtually straightening the deformations in a 3D graphic editor and completing the missing bone fragments. Later, this skeleton was printed life-size for a new exhibition at the Undorovsky Paleontological Museum.

Thanks to painstaking work carried out by an international team of paleontologists, Luskhan is now not only one of the most well-studied pliosaurs in the world, but also the only one with a complete virtual reconstruction. In the published article you can see recreated images of the ruler of the ancient seas.

Fischer V., Benson R.B.J., Zverkov N.G., Arkhangelsky M.S., Stenshin I.M., Uspensky G.N., Prilepskaya N.E. Anatomy and relationships of the bizarre Early Cretaceous pliosaurid Luskhan itilensis // Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2023. Volume 198, Issue 1, Pages 220–256. DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlac108