Leopards released at the end of July have mastered a significant part of the territory of North Ossetia, especially forest areas, but, judging by the data received, they are not going to stop there. The habitats formed by them during the snowless period began to undergo changes due to the onset of cold weather and the appearance of snow on the mountaintops.

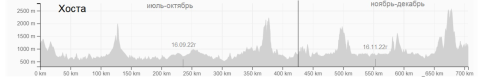

GPS locations obtained from the collars indicate that the female Khosta has travelled the longest path since release: she walked 707 km, swam across the river, crossed a large highway, and most of all she fell in love with forested gorges. In the snowless period (July-October), she covered a greater distance (429 km) than in late autumn and early winter (November-December) - 278 km. The total area that she has mastered is the largest compared to other leopards - 1353 sq. km, also differing before and after the beginning of November. Until the beginning of November, Khosta occupied 651 sq. km, then she moved and completely changed her place of residence - her new site is 439 sq. km and continues to grow.

In choosing the path, Khosta prefers a simpler terrain than her sister Laura - more gentle slopes, lowlands. For 5.5 months, Khosta only once rose to a height of 2500 m above sea level, and twice - to a height of 2000 m a.s.l., the rest of the time keeping to the foothill forests and rarely rising above 1000 m a.s.l. - just to make an estimation of her surroundings and return to lower ground. Life in these conditions probably determined the predominance of small but plentiful prey (badgers, jackals, raccoon dogs, forest cats and foxes) in Khosta’s diet, although deer became her last prey: after all, it got colder, the New Year is approaching, you can allow have a tasty and plentiful meal.

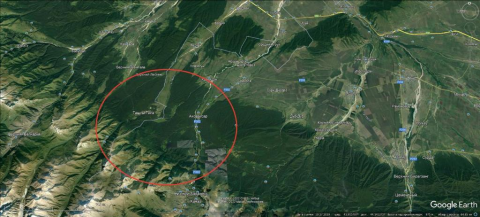

The champion in wild ungulates, of course, is Laura. Of the 20 potential places of her hunting, the specialists managed to check 14: they found the remains of 5 roe deer and one wild boar, the rest of the victims were wild small predators. At the same time, Laura seems to deliberately choose difficult areas for people to work - 2000-2500 m above sea level. (Fig. 1 a, b). Checking her hunting grounds often turns into a small expedition, fraught with unforeseen difficulties. In addition, she hunts more often than all other leopards (more on this below) and is likely the most well-fed.

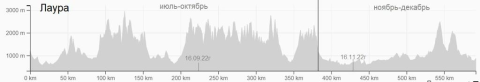

The territories that Laura has mastered can be described as predominantly steep slopes and rocky outcrops. And although during the time after the release, she travelled a shorter distance than Khosta (592 km), before the onset of cold weather she explored, for the most part, subalpine and alpine biotopes. Until the end of October, Laura walked 380 km and covered an area of 309 sq. km. When snow fell steadily on the mountain peaks and temperatures began to stay below zero, she descended into a snowless zone and went to neighbouring Kabardino-Balkaria, where she managed to catch a wild boar (Fig. 2a).

Since the beginning of November, Laura has covered only 220 km, but she has mastered a much larger area - 1027 sq. km. This female leopard, on the one hand, mastered various types of medium and large prey and hunting techniques in the wild more successfully (as evidenced by the distance travelled between hunts and the time of the hungry period). But on the other hand, in winter, she may have to face competitors more often (wolves, bears that did not go into hibernation) and either give up half-eaten prey to them, or eat it faster. For Khosta, who focuses on small prey and patrols lower areas, the problem of competition with the wolf and the bear should be less acute.

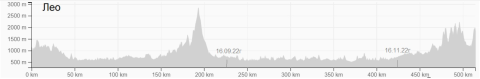

The male Leo has a comparatively easier time than females, since he is still much larger and, apparently, a calmer and more confident leopard. He prefers not to waste energy in vain. Unlike females, his habitat is more stable, and the area grows gradually and evenly. He does not deviate from his mastered areas sharply or take long journeys in search of unknown adventures. For 5.5 months, he walked 515 km and mastered 713 sq. km. If females are more likely to make sudden decisions about changing geoposition (in December, for example, Khosta crossed the Ardon and moved east, and Laura quite unexpectedly went to explore Kabardino-Balkaria, although before that she had no urge to go beyond the Turmonsky forest area), then Leo does not even try to explore mountain heights and prefers lowland forests as habitats (Fig. 3). 47% percent of his prey is made up of small carnivores, although he has been confirmed to successfully prey on both red deer and wild boar. He hunts with approximately the same frequency as Khosta (likely due to the fact that both animals use similar biotopes of foothill and low-mountain forests, Fig. 3c).

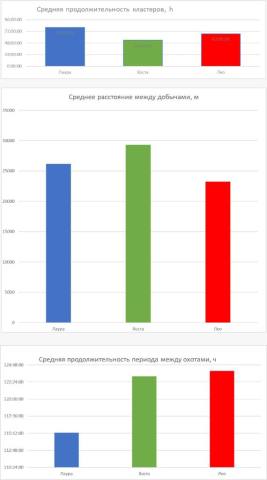

The distance that all leopards travel from prey to prey differs little (Fig. 4a). At the same time, it takes Laura the longest to eat her victims (Fig. 4b) and her prey is, on average, larger.

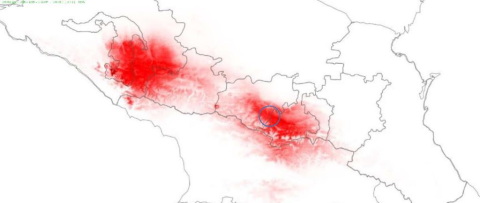

Since Laura, like some other leopards released earlier, set off from North Ossetia to Kabardino-Balkaria, we made another comparison - the paths they chose for such travel. It turned out that a clear corridor was visible, which most of them either used or chose to explore. So, Volna, Agura, Baksan and Laura were interested in this “green bridge” of the Central Caucasus (Fig. 5 a, b), and Volna and Laura went to the Kabardino-Balkarian expanses through it. This narrow strip of mountain forests is critical for the movement of leopards in the Central Caucasus, so agricultural land should in no case approach this strip closely enough to limit its passability from the impregnable sections of the mountain range. The results of snow leopard habitat suitability modelling that we published in 2020 confirm this (Fig. 5a).

The program for the restoration of the Persian leopard in the Caucasus is being implemented by the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources with the participation of the Sochi National Park, the Caucasian Reserve, the North Ossetian Reserve, the Alania National Park, the World Fund for Nature , the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEE RAS), the A.K. Tembotov Institute of Ecology of Mountainous Territories RAS, Moscow Zoo, with the assistance of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA). Funding for the monitoring of the Persian leopard in the Caucasus is supported financially by the World Wide Fund for Nature. In North Ossetia, RusHydro is providing financial support for the population recovery program.

Related materials:

Komsomolskaya Pravda: "Leopards spotted hunting in the mountains of the KBR"