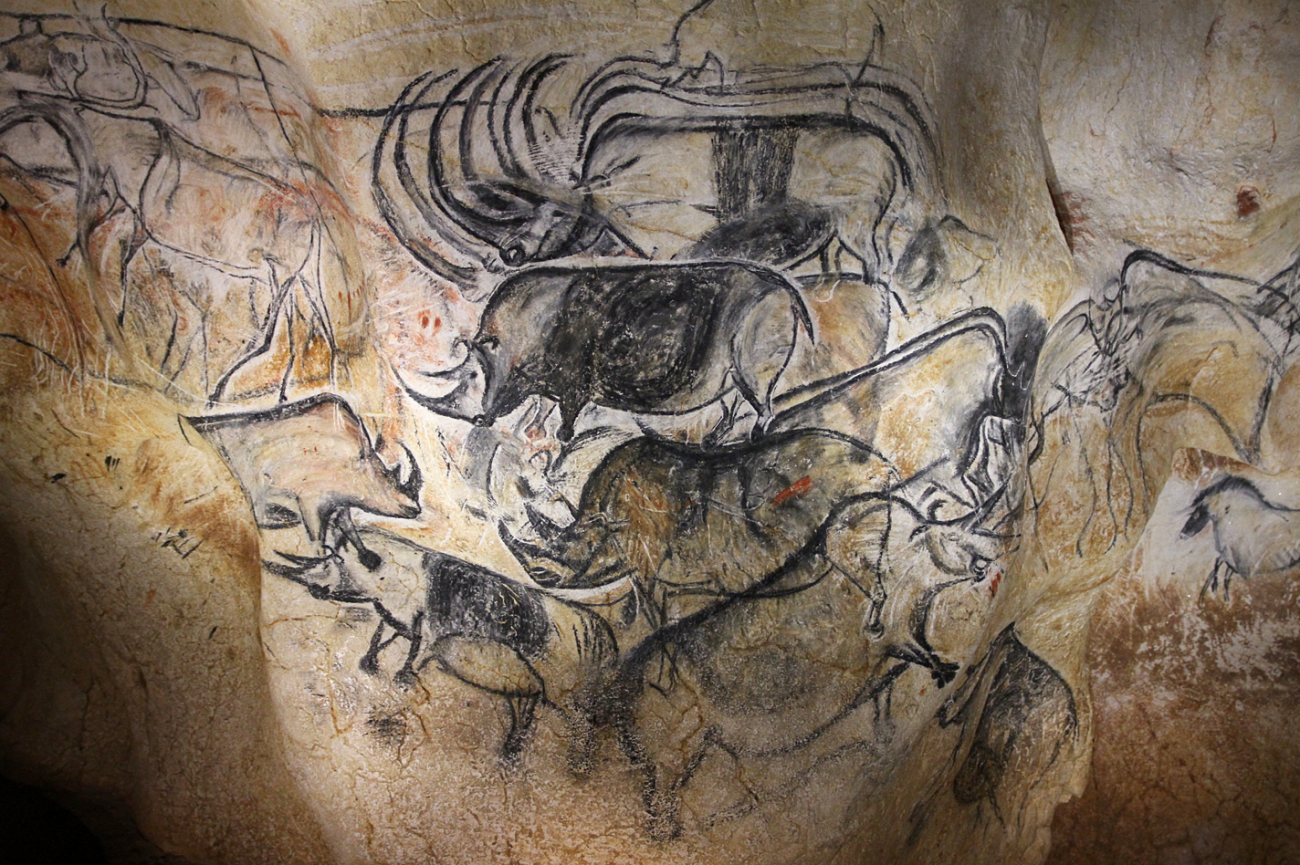

One of the unique pieces of evidence that allows us to judge the appearance of fossil animals of the late Pleistocene are their rock paintings left on the walls of caves by Paleolithic artists (Figure 1). In some cases, these images provide information about the length of the fur and its color, the presence or absence of some exterior details (for example, the mane of cave lions), and convey scenes of tournament fights among large ungulates and hunting scenes of predators through the millennia. However, rock paintings certainly cannot be considered photorealistic evidence, they often violate body proportions, do not depict the well-known fur coat in fossils, and simplify various anatomical details. One of the topics of discussion related to the appearance of representatives of the mammoth fauna, which has caused controversy among researchers and paleontology enthusiasts for many years, is related to numerous images of woolly rhinoceroses (Coelodonta antiquitatis) with a large hump in the neck and withers area (Figure 1). Finds of mummies of these rhinoceroses contradicted the existence of this anatomical feature. Both mummies, found at the beginning of the last century in bitumen-ozokerite deposits near the village of Starunya (Ukraine), did not have humps. The rhinoceros mummy found in the lower reaches of the Kolyma River had damaged neck and withers area, but the general outline of the body did not show even a hint of a large hump. Everything indicated that the rock paintings were just artistic exaggerations.

However, in 2020, a new mummy of C. antiquitatis was discovered on the banks of the Tirekhtyakh River (Yakutia), which was named the Abyi Rhinoceros (Figure 2). The carcass belonged to a 4-4.5-year-old teenager who had lain in the permafrost for over 32 thousand years, and the most unexpected detail of the find was that there was a clearly visible hump in the neck and withers of the rhinoceros. In a joint article published in Quaternary Science Reviews, Ruslan Belyaev and Nadezhda Kryukova, employees of the Laboratory of Ecology, Physiology and Functional Morphology of Higher Vertebrates at the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IPEE RAS), together with colleagues from Yakutia under the supervision of Gennady Boeskorov (IGABM SB RAS), studied the anatomical features of the mummy found. But before we move on to discussing the new find, it is worth answering the question: do modern rhinos have humps?

Of the five species that have survived to this day, we have only one example of a rhino with a hump – the African white rhinoceros. The hump in this species is located in the neck and front part of the withers, and is traditionally called the “nuchal hump” in scientific literature. Structurally, the hump of the white rhinoceros consists of three parts: thickened skin (reaching 5 cm), a thin layer of fat (about 3 cm), and hypertrophied nuchal ligament and dorsal muscles of the neck, which form the bulk of the hump. Are the humps of the woolly rhinoceros similar to those of its modern relative?

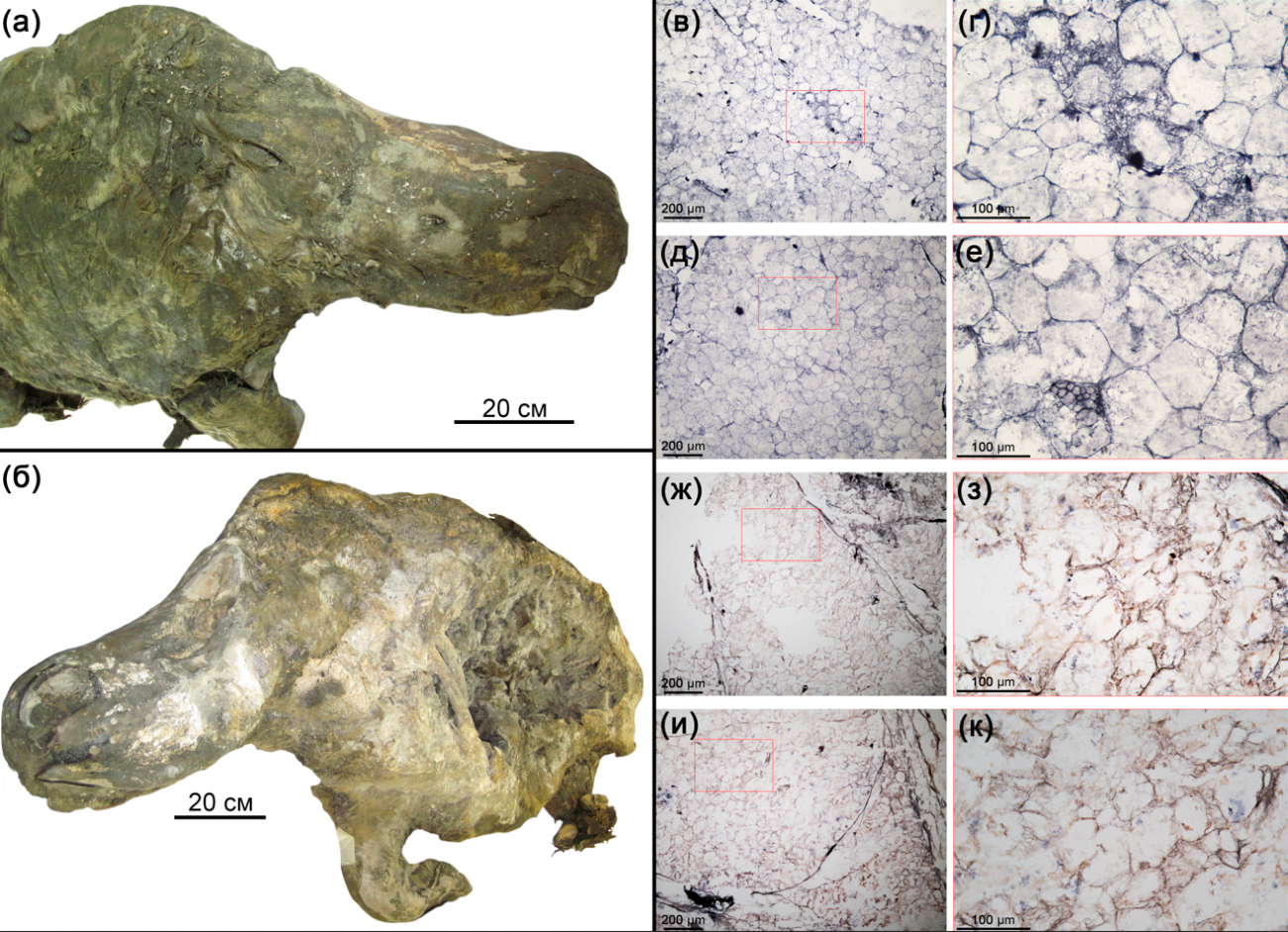

The hump of the woolly rhinoceros and its African relative is located almost identically: it occupies the space between the back of the head and the tops of the shoulder blades (Figure 2, 3). The thickness of the skin in the studied juvenile exceeds 1 cm, but the main volume of the hump is formed by fatty tissue. The size of the fat deposits reaches about 40 cm in length, 13 cm in height and 14 cm in width. Considering that the fatty tissue is strongly dehydrated, the hump dimensions during life should have been larger. The thickness of the subcutaneous fat in the studied rhinoceros reached 1-1.5 cm in the neck and back, and 1.5-3 cm in the chest. The results of the histological study suggest that the fat filling the hump is most likely white, not brown (Figure 3).

It is interesting to note that, in addition to the woolly rhinoceros, a fatty hump was previously discovered in another largest representative of the mammoth fauna - the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). As in the case of rhinoceroses, modern elephants do not have a fatty hump, as well as other large fat deposits confined to any specific part of the body. What was the functional load of these structures in the largest representatives of the fauna of the Ice Age? To answer this question, it is necessary to first note that one of two main types of fat could accumulate in the hump: brown or white. White fat performs a number of functions in the body, but first of all, it is responsible for the reserve of nutrients in the form of fat droplets. Brown fat contains a huge number of mitochondria, which allows it to implement its key function - thermogenesis (heat production). Brown fat is present in large quantities in newborn mammals. Among large mammals living in extremely cold environments, brown fat is present in large quantities in newborn musk oxen and plays a key role in survival during long and very cold winters.

An adaptation similar to that of musk oxen was probably also characteristic of woolly mammoths. Histological analysis of fat deposits in the baby mammoth Lyuba (aged about one month) showed that it was brown fat deposits in the hump. However, our data for the juvenile woolly rhinoceros show that its hump was probably filled with white fat. This may indicate both differences in the functional significance of the humps in mammoths and rhinoceroses, and the degeneration of fat tissue from brown to white with age. This phenomenon is well known for modern mammals, but has not been studied at all for representatives of the mammoth fauna.

In addition to the first discovery of a hump in a woolly rhinoceros, the study raised many new questions. Was the hump seasonal in rhinos? Could fatty tissue accumulate during the warm season and be completely consumed during the cold season? Was there a transition from a hump filled with brown fat and responsible for thermogenesis in young rhinos to a hump filled with white fat and responsible for nutrient storage in adults? Could the white fatty tissue in the hump turn brown with the onset of autumn and winter cold? New finds and new studies will undoubtedly allow us to answer these questions and fill in the gaps in our understanding of the anatomy, physiology and lifestyle of the largest representatives of the mammoth fauna.

Article published by: Gennady G. Boeskorov, Marina V. Shchelchkova, Albert V. Protopopov, Nadezhda V. Kryukova & Ruslan I. Belyaev (2024) Reshaping a woolly rhinoceros: Discovery of a fat hump on its back. Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 345, 109013.

Related materials:

Innovation world news: "It happened: Russian scientists found a hump on a woolly rhinoceros"

Yakutia news feed: "Ancient rhinoceros from Yakutia stored fat in its back hump"

Science.rf: "Ancient rhinoceros from Yakutia stored fat in its back hump"