How do animals' lives change in the fall? How does hibernation differ from regular sleep? Where do birds fly away? And which animals' brains shrink in the fall? Doctor of Biological Sciences, Scientific Secretary of the IEE RAS Natalia Feoktistova and PhD in Biological Sciences, Senior Researcher at the IEE RAS Bird Ringing Center Sergei Volkov told the Nauka.rf portal about this.

First, the winter stocks

It all starts with the change in daylight hours, which serves as the main signal for animals about the onset of the autumn-winter period. The days are getting shorter, which means it's time to prepare for the cold. And here everyone will have their own strategy. Some mammals hibernate, others go into a short torpor - a short period of numbness. It is believed that these methods allow you to save energy. However, many species maintain an active lifestyle, finding enough food even in winter conditions.

"In central Russia, hibernation in its various forms is demonstrated by a number of rodent and carnivore species, some insectivores, and bats. Those that always hibernate (the so-called obligate hibernators), including marmots, gophers, jerboas, hedgehogs, and bats, accumulate fat reserves by autumn, prepare winter shelters for themselves, or move to suitable ones," says Natalya Feoktistova, Doctor of Biological Sciences and Scientific Secretary of the A. N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences. While some animals strive to accumulate fat mass, others prefer to make reserves in their burrows, for example, hamsters. But this does not mean that they will necessarily eat the prepared food later.

"It was previously believed that animals store food in order to eat in burrows in winter. But this does not always happen. "Let's say if spring is late and the animal comes to the surface and does not find food there, it can really eat its reserves. But if spring has come on time, it may not use the food at all," the biologist explains.

"Wrong" sleep

Hibernation is not that simple either. Thanks to modern technology, scientists have found out that it is not at all like the standard sleep that we can imagine. This is a unique state in which there is no place for any sleep at all, and in which the body temperature of animals drops sharply. Using special devices - thermal accumulators - researchers have found that the temperature of some species of gophers and hedgehogs during hibernation can be below 0°C. "In fact, hibernation is living death. No electrical processes are detected in the brain at temperatures below 15°C," says Natalia Feoktistova.

There is another popular misconception associated with this unusual state. It is believed that hibernation lasts continuously, on average from October to March. In fact, approximately every ten days or two weeks, hibernating animals raise their body temperature to normal, about 37°C. They remain in this state of normothermia for several hours, and then again plunge into torpor. The body temperature drops to +4 - 5°C, and sometimes to 1°C and even to 0 and -0.5 °C. Similar low temperatures have been found in different species of hedgehogs and arctic ground squirrels. The latter have the longest hibernation episodes - about three weeks.

This phenomenon still raises questions among biologists. After all, in order to wake up and quickly raise the temperature, you probably need to spend as much energy as is saved during hibernation. Why animals need to periodically wake up and what triggers this process, scientists have yet to determine.

"Perhaps it all has to do with the peculiarities of the nervous system, which cannot remain in a state of "coma" for a long time and is responsible for the rise. However, to confirm this hypothesis, more research is needed," the specialist believes.

Superpowers

Not all animals fall into such a classic hibernation. Some predators, including bears, have a similar state called "winter sleep": their body temperature hardly changes, but they spend almost five months practically lying on "one side" and absolutely not eating or eliminating metabolic waste. But there are exceptions. For example, bears that are too slow to accumulate reserves by winter still have to sometimes leave their dens in search of food.

"In addition to hibernation, there are many other intermediate options. For example, torpor, which lasts several hours on average. Sometimes it occurs daily, usually in the morning. In animals in this state, metabolism slows down, although not as much as during hibernation, and body temperature drops to 18-20°C," notes Natalia Feoktistova.

Djungarian hamsters, in particular, can fall into a state of torpor. In the wild, these animals weighing only about 30 grams can be found in the south of Western Siberia, in the Minusinsk Basin (away from their main habitat), as well as in Northern, Central and Eastern Kazakhstan. With the onset of cold weather, they, like white hares, change their color from dark to white. Such camouflage allows the animals to leave their burrows and be barely noticeable in the snow, hiding from predators.

Some mammals, including voles, mice and shrews, prefer to remain active in winter. Moreover, while some animals accumulate body weight for winter, these animals, on the contrary, lose weight. These changes also occur in species that enter torpor, such as the already mentioned Djungarian hamsters or their relatives, Campbell's hamsters.

Another rather interesting feature is observed in autumn in some species of shrews. By winter, not only their body weight decreases, but also their cranium (by an average of 15%). In spring, it returns to normal size. This phenomenon, described back in 1949, is called the Dehnel effect. These, at first glance, “unnatural” changes for shrews are actually justified: the smaller the animal, the less food it requires. In winter, when food may be in short supply (and they feed on invertebrates), this “superpower” helps them survive.

Heading south

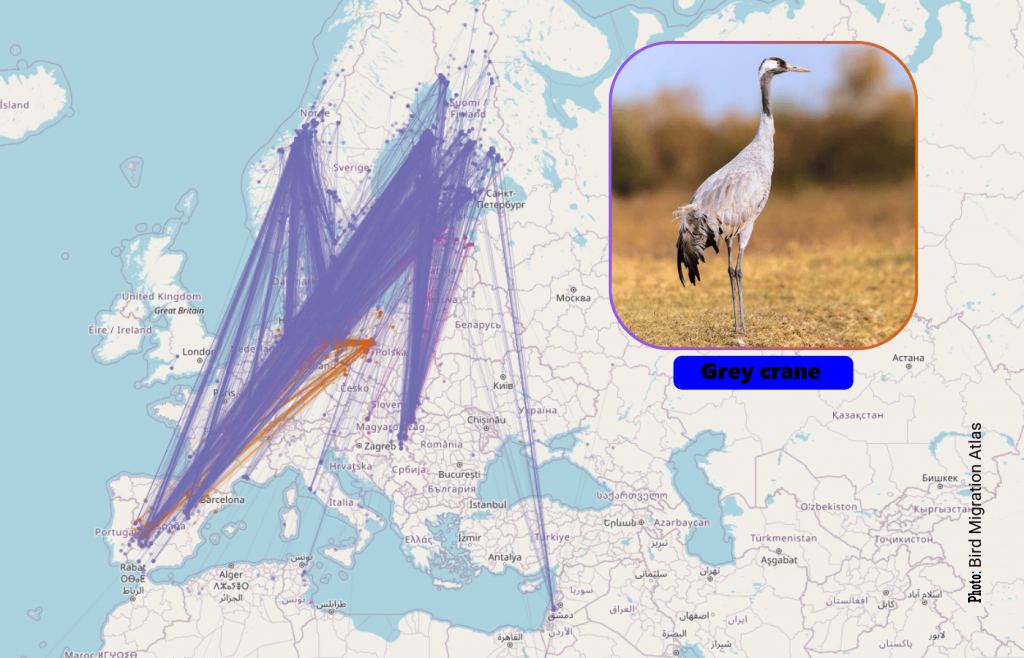

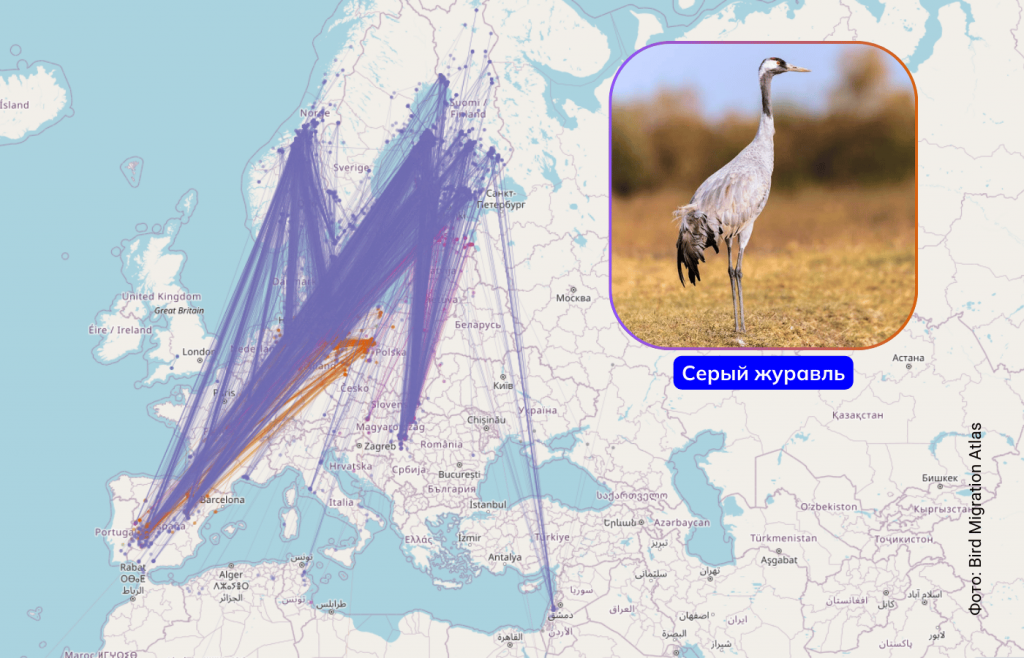

For many birds, the onset of autumn is associated with the migration period. Cranes, ducks, swans, starlings, thrushes, larks, rooks, as well as swallows and other species of the passerine family prefer to spend the winter in warm countries. “A total of about 400-450 bird species live in the European part of Russia. Of these, only about ten percent stay for the winter, that is, about 30-40 species. The most popular destination for these migrating birds is considered to be Northern or Eastern Africa,” says Sergey Volkov, PhD in Biology and Senior Researcher at the Bird Ringing Center of the Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Swifts are among the first to leave their native lands. You can notice a flock of these birds flying south in the sky as early as mid-August. Ducks and swans leave later, when the thermometer drops to subzero temperatures.

“Migration is a fairly energy-consuming stage in the life of birds. In autumn, it happens quickly and takes up to 20 days on average. Much depends on the presence of offspring. For example, if the bean cranes — waterfowl from the duck family — already have chicks, then their joint flight will take about a month, including stops. Without offspring, adults are able to cover the distance in 3-4 days,” the specialist shares.

Today, thanks to GPS transmitters, ornithologists can accurately track the movements of birds in real time and find out where they stop. During one of these studies, scientists were able to determine that every year the route to the African continent may differ even for the same individuals. And for some species, the destination itself changes over time.

For example, gray cranes usually winter in North-East Africa, in particular, Ethiopia and Sudan, or in Israel. But in years when the winter is warm, the migration route of the birds is shortened, and they can be found in the Krasnodar Territory, Stavropol Territory and Crimea.

"If the warming continues, then, most likely, we will have regular wintering places for birds that are, for now, forced to migrate to warmer regions. Let's see how much the climate changes. The last few years, our winters have been harsh. In such conditions, wintering is, of course, impossible for most species," comments Sergey Volkov.

With or without a transfer

The route to the southern countries sometimes does not go without stops. One of the most important places for migrating birds is Lake Manych-Gudilo, located in the south of Russia, on the territory of three regions: Kalmykia, Stavropol Krai and Rostov Oblast. Here you can meet various species of gulls, herons, cranes, geese, ducks and passerines. As well as rarer species, including the whooper swan, which lives in the forest-tundra and taiga zones.

At this large reservoir, birds can gather strength and accumulate reserves to then make a long flight over the Black or Caspian Sea. Many migration stops are known in the Astrakhan Region and the Republic of Dagestan.

According to Sergey Volkov, many birds migrate on a wide front, but in this flow there are points of attraction associated with large lakes, swamps and the sea coast. Now they are trying to organize protected areas on their route in order to disturb the inhabitants less and discourage poachers.

The path is set

How do birds even know where to fly? Unfortunately, scientists cannot yet give a single answer to this question, since this knowledge and skills arise differently in all species.

For example, it is known that crane and goose chicks travel with their parents, thanks to which they learn about the route and wintering places. In small birds such as waders or passerines, the parents fly away earlier than the young. It is assumed that the directions of some species can be laid down at the genetic level, but this hypothesis has yet to be tested.

However, scientists have still managed to learn something interesting. It turns out that migrating birds have their own magnetic compass system, with the help of which they navigate. This is discussed in more detail in a study by the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

One of the recent experiments also showed that birds have a special protein with the help of which they navigate in space through magnetic fields, and a separate part of the brain is responsible for creating a route - the medial pallium. To confirm this, Japanese ornithologists attached special devices to pallium birds that tracked the work of the pallium in flight. As soon as the protein in the birds' brains and eyes detected magnetic waves, this area of the brain developed a route along them. Moreover, the cells in this area became active when the birds turned north.

Home is best

There are also birds that prefer not to fly anywhere and spend the winter in their native lands. Sedentary birds include, in particular, nuthatches, pikas, woodpeckers and most species of tits. Gray crows also remain in the city, but most of the "wild", non-urban crows migrate further south, to the Non-Black Earth Region (an agricultural and industrial region of the European part of Russia).

In fact, these birds can also migrate, but only over short distances and only during periods of severe frost and in case of food shortage. As a rule, they survive alone, but in order to survive harsh conditions, they sometimes gather in flocks. It is believed that this strategy helps them find insects that hide under the bark and in the cracks of trees.

Pigeons are also homebodies. Interestingly, these birds originally lived in the southern regions of the country, but over the years they settled in urban areas with low-rise buildings.

"Pigeons adapt well to many conditions. You may notice that there are practically no pigeons in villages or wild areas. This is because they are much more comfortable in cities: there is enough food, so they can nest all year round. Although, in general, birds normally have only one or two broods per season. After nesting, there comes a period when the birds must fly away. But since pigeons do not migrate, they nest all year round, during which they can have up to five broods. Moreover, some pairs manage to nest even in winter. This is the influence that cities have on them," explains Sergey Volkov.

According to the expert, the development of infrastructure in general has had a significant impact on the behavior of birds. In addition to pigeons, other birds also move increasingly closer to cities, because here they have a better chance of finding food.

“One of the trends is that birds have become less shy. Many people are positive about them, so large flocks of mallards or shelducks can often be found on city ponds. Feeding and installing feeders play a major role in this. In addition, the number of hunters is noticeably decreasing, which is good news. Birdwatching, a hobby that is attracting an increasing number of fans, is developing. People are becoming more attentive to nature, and this also affects the behavior of birds,” the expert concludes.