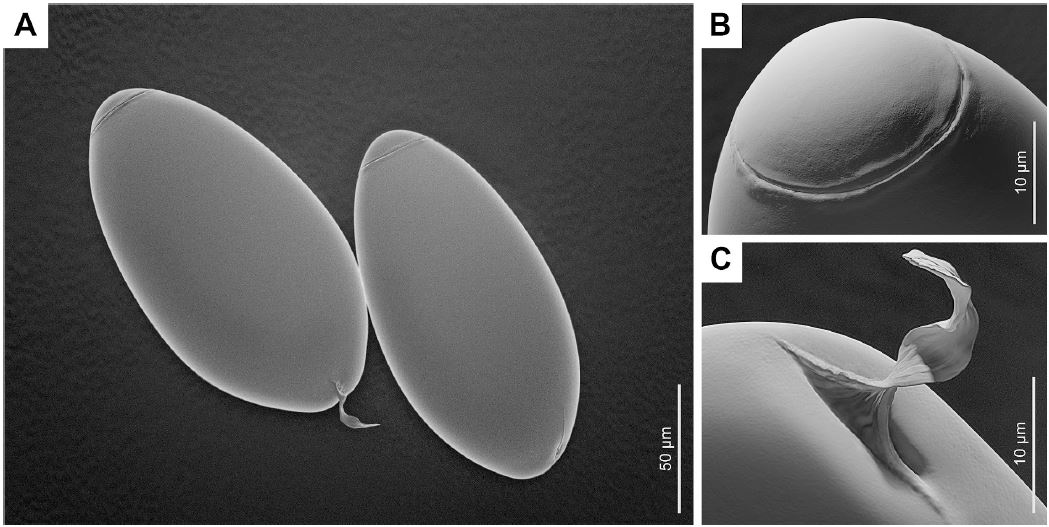

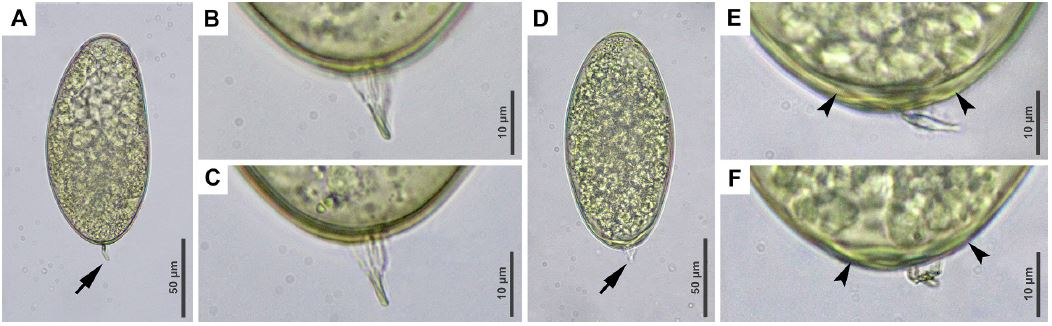

A team of Russian researchers took a closer look at the liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica Linnaeus, 1758). This parasitic worm that inhabits the bile ducts of the liver of herbivores and humans is known throughout the world. Fasciola has been found on all inhabited continents and causes a lot of trouble for humane and veterinary doctors and their patients. The main and simplest method of intravital diagnostics of fascioliasis is coproovoscopy, that is, the detection of fasciola eggs in the excrement of the host. It would seem that the morphology of the egg should have been studied in detail over the past centuries. However, it turned out that this is not the case. When examining a zoo reindeer, scientists found eggs that by all appearances resembled fasciola eggs with one exception. Some of these eggs had "tails". A similar feature was described by the Russian researcher D. F. Sinitsyn at the beginning of the last century for a related helminth, the giant liver fluke (Fascioloides magna). Moreover, Sinitsyn claimed that this feature helps to reliably distinguish these helminths. And it is necessary to distinguish them, because the giant (or American) fluke is indeed much larger and lives not in the ducts, but in the parenchyma of the liver, which affects the choice of treatment. Even more paradoxically, Sinitsyn studied both types of liver flukes, but noticed "tails" only in one.

To clarify the diagnosis, the researchers isolated and analyzed DNA from the "tailed" helminth eggs obtained from a deer and, at the same time, obtained adult fasciola individuals from a slaughterhouse (from the liver of a bull). The eggs obtained from adult flukes were also equipped with "tails" in about a quarter of cases. It is likely that D. F. Sinitsyn, who studied flukes in Russia and the USA, obtained eggs using different methods. It is known that when using sieves, the "tails" easily break off, unlike the method of successive washings.

Thus, it was possible to establish that fasciola eggs in some cases are just as "tailed" as fascioloides eggs, and they cannot be distinguished by this feature. In addition, the thickening of the egg wall at the pole where the "tail" is found also occurs in both types of flukes, and also cannot serve as a differential criterion. To demonstrate the discovered morphological features, the authors turned to a 3D modeling artist to create three-dimensional images of fasciola eggs. OBJ files of 3D models of F. hepatica eggs (with and without "tails") are available to everyone at the link.

In addition, molecular phylogenetic methods confirmed the rightful place of reindeer in the list of definitive hosts of fasciola.

Another egg, which by all criteria fits the description of an F. hepatica egg, was found in a wild reindeer from Severny Island, Novaya Zemlya. Of course, more research is needed, but this may be the northernmost focus of fascioliasis in the world.

The obtained descriptions and images reflect in detail the morphology of liver fluke eggs and should help doctors, veterinarians and biologists around the world in diagnosing fascioliasis.

On behalf of the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the following employees of the Laboratory of Taxonomy and Evolution of Parasites of the Parasitology Center participated in the work: Olga Aleksandrovna Loginova, Boris Dmitrievich Efeikin and Sergey Eduardovich Spiridonov. They were assisted by colleagues from the St. Petersburg University of Veterinary Medicine (Anna Alekseevna Krutikova), the Russian Arctic National Park and the N.P. Laverov Federal Research Center for Comprehensive Study of the Arctic, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Ivan Andreevich Mizin).

The article was published in open access mode in the journal Food and Waterborne Parasitology (Q1).