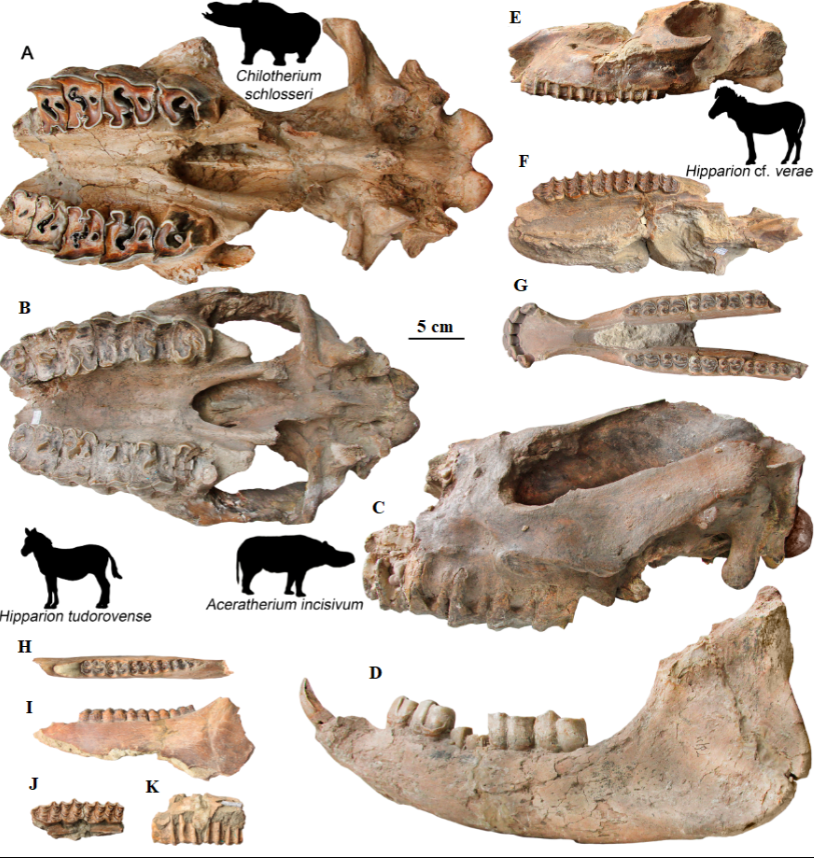

In a new study published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, employees of the Laboratory of Ecology, Physiology and Functional Morphology of Higher Vertebrates at the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution RAS Ruslan Belyaev and Natalya Prilepskaya, together with their colleagues from the Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social and the V.I. Vernadsky State Geological Museum RAS, studied the feeding habits of carnivorous and ungulate mammals that inhabited the territory of the Northern Black Sea region in the Late Miocene. The unique collection of skulls, lower jaws and individual teeth studied in the work (Fig. 1) was assembled at the beginning of the 19th century by the Tiraspol icon painter and fossil hunter F.V. Frolov at the locations of the “hipparion fauna” discovered by him: Grebeniki (Ukraine), Chobruchi and Tudorovo (Moldova). The remains of the animals were collected by Frolov for sale to Moscow and Odessa Universities. Subsequently, the collection of the Geological Cabinet of the Imperial Moscow University passed into the funds of the V.I. Vernadsky Geological Museum, in which it is stored today. The age of the studied fossils corresponds to the end of the Tortonian (Grebeniki and Chobruchi ~8-7.5 million years ago) and the middle Messinian centuries (Tudorovo ~6.5 million years ago) of the Neogene period.

The “Hipparion fauna”, named after the genus of Neogene three-toed horses, in the Northern Black Sea region was represented by elephants (Deinotherium and Stegodon), hornless rhinoceroses from the subfamily Aceratheriinae (Fig. 1), antelopes, camels, giraffes, bulls and horses, aardvarks, primates, saber-toothed cats from the subfamily Machairodontinae, hyenas and civets, as well as ostriches. But how could these animals, which we associate with the African savannah and equatorial forests, inhabit the territory of the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions? The answer to this question is connected to climate change. Moreover, the appearance and spread of the hipparion fauna is associated not with climate warming, but with the cooling and drying of the region.

The Miocene (23.0–5.3 Ma) was the last episode of warm climate at the planetary level, and its middle part was the warmest period in the entire Neogene. Thus, the average annual temperature in Eastern Europe was 15-18°C, and the average winter temperature was 7-12.5°C. The Middle Miocene flora of the East European Plain was dominated by extremely diverse and taxonomically rich forests: deciduous forests with various species of walnut, elm and beech, evergreens (including myrtle, laurel, magnolia), tree ferns and vines. Among the conifers, taxodium and sequoia remained. However, at the end of the Middle Miocene, a noticeable cooling and drying of the climate occurs. A decrease in the average annual temperature by more than 5°C opens the Tortonian Age in the lowland areas of the Northern Black Sea region. Along with the cooling and drying of the climate, purely herbaceous biotopes appear in the landscape. The regression of the huge Eastern Paratethys basin (the remnants of which are the Black, Azov, Aral and Caspian Seas) drains large areas of the shelf, which are immediately occupied by halophilic land plants. Amaranthaceae and wormwood begin to play a significant role, and in some places even dominate in the palynological spectra. In the late Miocene (~10-9 million years ago), the zone of continuous forests was divided into separate massifs, forests first disappear from watersheds, being replaced by open forests and remaining only in river valleys, and then in the open spaces between rivers there is a change from open forests to savanna-steppes, first prairie meadow type, and then dry.

Climate and landscape changes in the region have been accompanied by changes in animal communities. The fauna of forest mammals, named after the small primitive horses of the genus Anchitherium the “anchitherium fauna”, is gradually replaced by the “hipparion fauna” of open spaces. By the end of the Tortonian, to which the faunas of the studied localities of Grebeniki and Chobruchi belong, the share of relicts of the anchiterium fauna in the communities of large mammals drops to 20%. As a result, in the Late Miocene of the Northern Black Sea region, an ecosystem most similar to that of the modern African savannah was formed.

In order to study the feeding habits of fossil carnivores and ungulates, methods for analyzing meso- and microwear of tooth enamel, well established on modern mammals, were used. Both of these approaches make it possible to obtain reliable data for determining the diet of mammals over two different time periods - the average annual and the last weeks of life. Mesowear of teeth is based on assessing the morphology of the relief of the chewing surface of the tooth and allows us to assess the abrasiveness of food of ungulate mammals over long time periods. Tooth microwear analysis is based on counting the number of enamel microdamages on the chewing surface of teeth and is used to study both ungulates and carnivorous mammals. Observed wear patterns vary greatly depending on the food consumed, allowing the distinction between mammals specialized for different food sources.

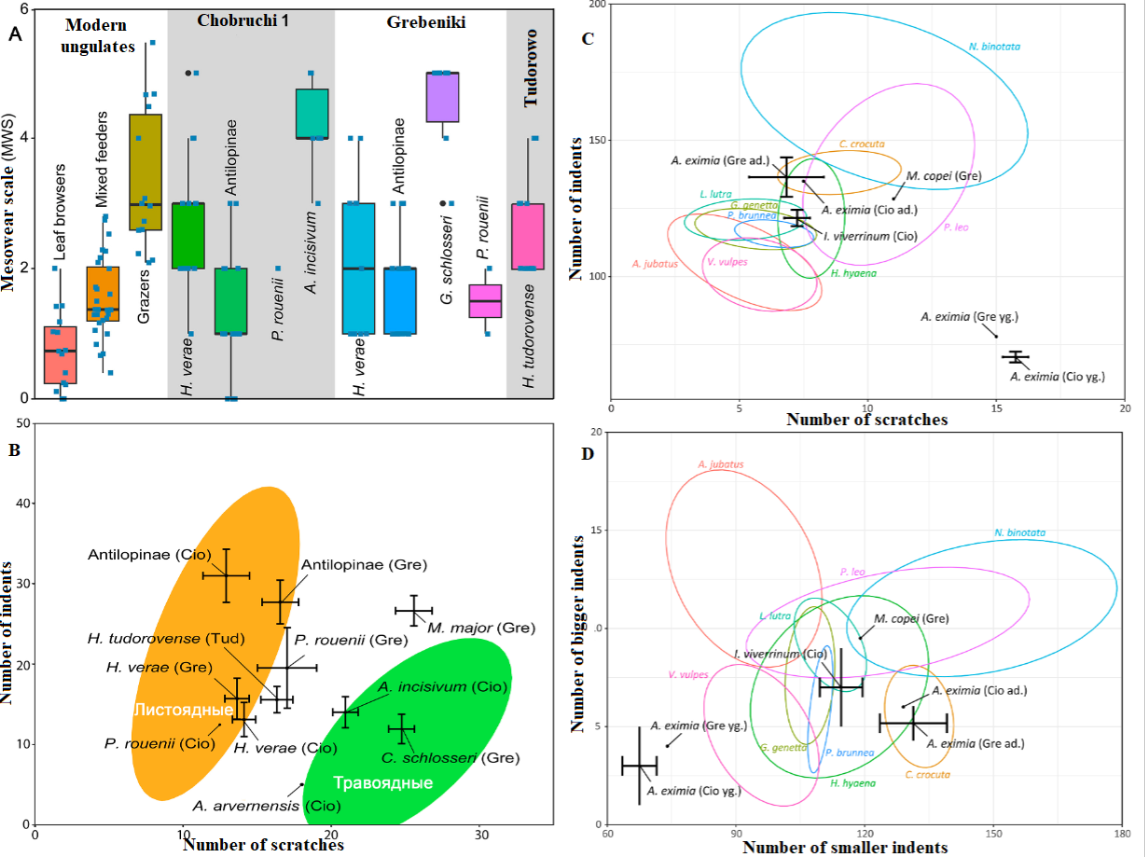

How similar was the diet of mammals in the modern and Neogene savanna? Most ungulates inhabiting savannah and woodlands in today's Africa are, to one degree or another, specialized in feeding on grass. The ungulates that inhabited the Late Miocene savanna of the Northern Black Sea region, on the contrary, were mostly leaf-eaters (Fig. 2). Thus, in the communities of herbivorous mammals from the large localities of Grebeniki and Chobruchi 1, foliage was characteristic of 65.3% and 82.8% of the studied individuals, respectively. This may indicate that specialization to a new food source (herbaceous plants that began to dominate the flora of the region) in ungulate mammals is somewhat delayed compared to changes in the landscape. At the same time, the studied material shows how in the late Miocene of the Northern Black Sea region there was a shift in the nutrition of hipparions from pure foliage (~8-7.5 million years ago) to a mixed diet of foliage and grass (~6.5 million years ago).

Did any of the Late Miocene ungulates of the Northern Black Sea region manage to fully master feeding on grass? Yes, the study showed that hornless rhinoceroses from the genera Chilotherium and Aceratherium were herbivorous (Fig. 2). In addition to the conclusion about the nature of nutrition for hornless rhinoceroses, it was possible to confirm the hypothesis about the herd lifestyle of these animals. The variability in tooth wear indicates that the formation of both localities with numerous remains of hornless rhinoceroses (Grebeniki and Chobruchi 1) corresponds to short-term catastrophic events. The sudden death of a large number of rhinoceroses in a small area of territory indicates that these ungulates were characterized by living in fairly large permanent groups. It is interesting to note that among modern rhinoceroses, living in large permanent groups, as well as specialized feeding on grass, is characteristic only of white rhinoceroses.

When studying predators, it was shown that the pattern of tooth wear in the mahairod (a large saber-toothed cat) was most similar to that of modern lions, indicating a specialization for feeding on the meat of large animals. Tooth wear in the most common Neogene hyenas of the genus Adcrocuta was found to be similar to that of the largest living hyena, the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), as well as the fossil cave hyenas C. spelaea and C. ultima ussurica. This is especially interesting because, unlike other modern hyenas, the spotted hyena is an active predator that hunts as much as a lion, and is also capable of very effectively chewing even the thickest bones, digesting cartilage, tendons and bones. At the same time, microwear of teeth in young individuals of A. eximia differed significantly from adults; moreover, the noted pattern does not overlap with any of the carnivorous species studied to date. Significant differences in microwear between juveniles and adults of Adcrocuta must have had a behavioral basis. However, currently available data do not allow reliable interpretation of these differences. As a hypothesis, it can be assumed that it was not typical for adult Adcrocutus to carry the carcasses of killed ungulates into their shelters, as modern spotted hyenas do, and as a result, it was less common for the cubs to play and chew bones.

Source: Florent Rivals, Ruslan I. Belyaev, Vera B. Basova, Natalya E. Prilepskaya. (2024) A tale from the Neogene savanna: Paleoecology of the hipparion fauna in the northern Black Sea region during the late Miocene // Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 112133, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2024.112133