Coral reef ecosystems are famous for their richness and diversity; from time immemorial, they have provided food and other resources to millions of people living in tropical countries. However, coral ecosystems are currently undergoing rapid degradation. Between the late 1960s and the late 2000s alone, the area of coral reefs decreased by approximately half.

So what is causing reef degradation?

Both natural and anthropogenic factors are to blame for this: increased water temperature, acidity, concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus salts, sedimentation, outbreaks in the number of predatory starfish and mollusks, overfishing, and the development of macroalgae. The list goes on.

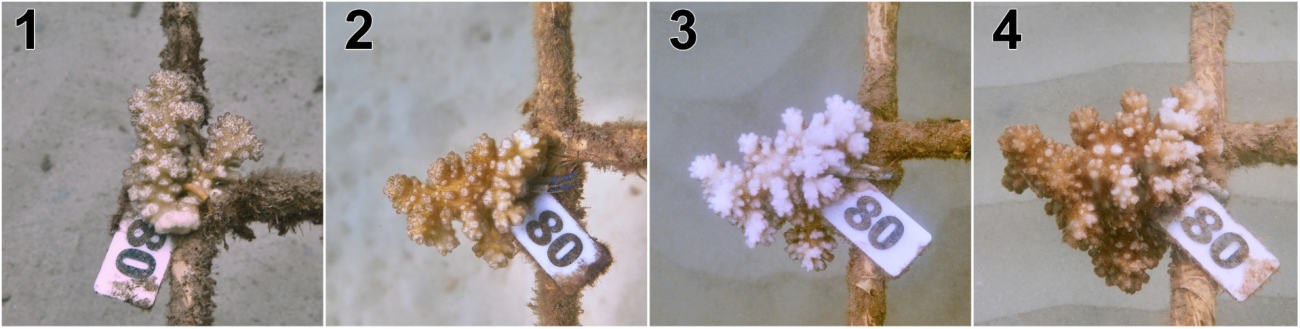

The most well-known cause of reef degradation is coral bleaching. This is the process by which symbiotic algae are released from the body cavity of the coral polyp into the water (Figure 1). Coral nutrition is largely provided by these microscopic algae, so bleaching weakens the coral, and severe, prolonged bleaching often leads to its death. Numerous articles and books are devoted to the study of intense bleaching, while two less pronounced, but no less significant processes for the coral reef - seasonal bleaching and partial mortality - remain in the shadows.

Corals around the world appear to experience seasonal bleaching as a natural response of symbiotic algae to changes in environmental factors such as temperature and light. However, even minor seasonal bleaching weakens the coral, which can lead to its death if the bleaching process is prolonged.

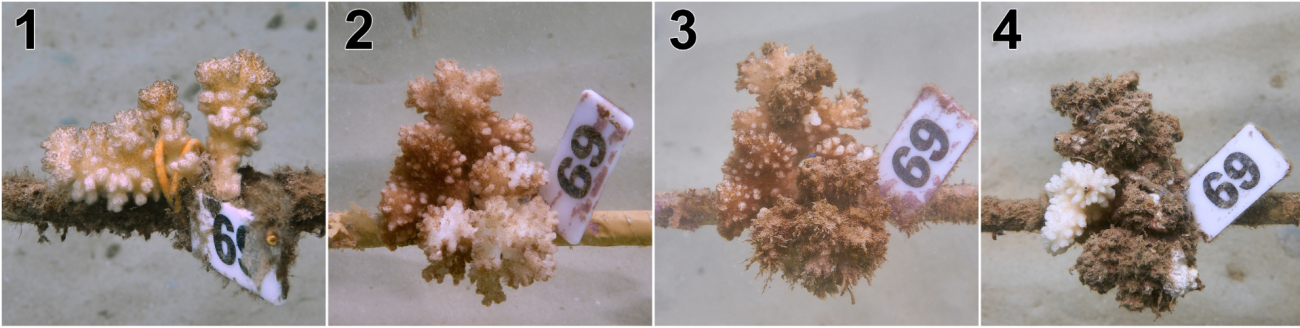

Partial mortality is the death of the coral surface that occurs for various reasons, for example, due to mechanical damage to the coral colony due to the bites of coral-eating fish or hard grains of sand during storms. The resulting areas of exposed coral skeleton can be regrown with tissue, but if this process is slow, they are colonized by macroalgae. Algae release metabolites that are toxic to corals, causing the damaged area to grow. Under natural conditions, the process of coral fouling is controlled by phytophagous fish, but if these fish are absent or few due to overfishing, the balance shifts in favor of algae. As a result, the affected area expands more and more, gradually taking over the entire colony, which ultimately leads to its death.

Until recently, only a few scattered studies were devoted to investigating the causes of seasonal bleaching and partial mortality, and the relationship between seasonal bleaching, partial mortality and coral mortality was not studied at all. Filling this gap was the goal of the study by a group of employees of the Laboratory of Morphology and Ecology of Marine Invertebrates of the Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences under the leadership of Temir Alanovich Britaev.

The work was carried out at the Dam Bay Marine Research Station, located in Nha Trang Bay (Vietnam). During the study, the state of the environment was monitored daily, in particular water temperature, precipitation intensity and wind speed (the latter factor was chosen as an indirect indicator of storms in the station area), and the condition of Pocillopora verrucosa corals planted at a testing site near the station was recorded twice a month.

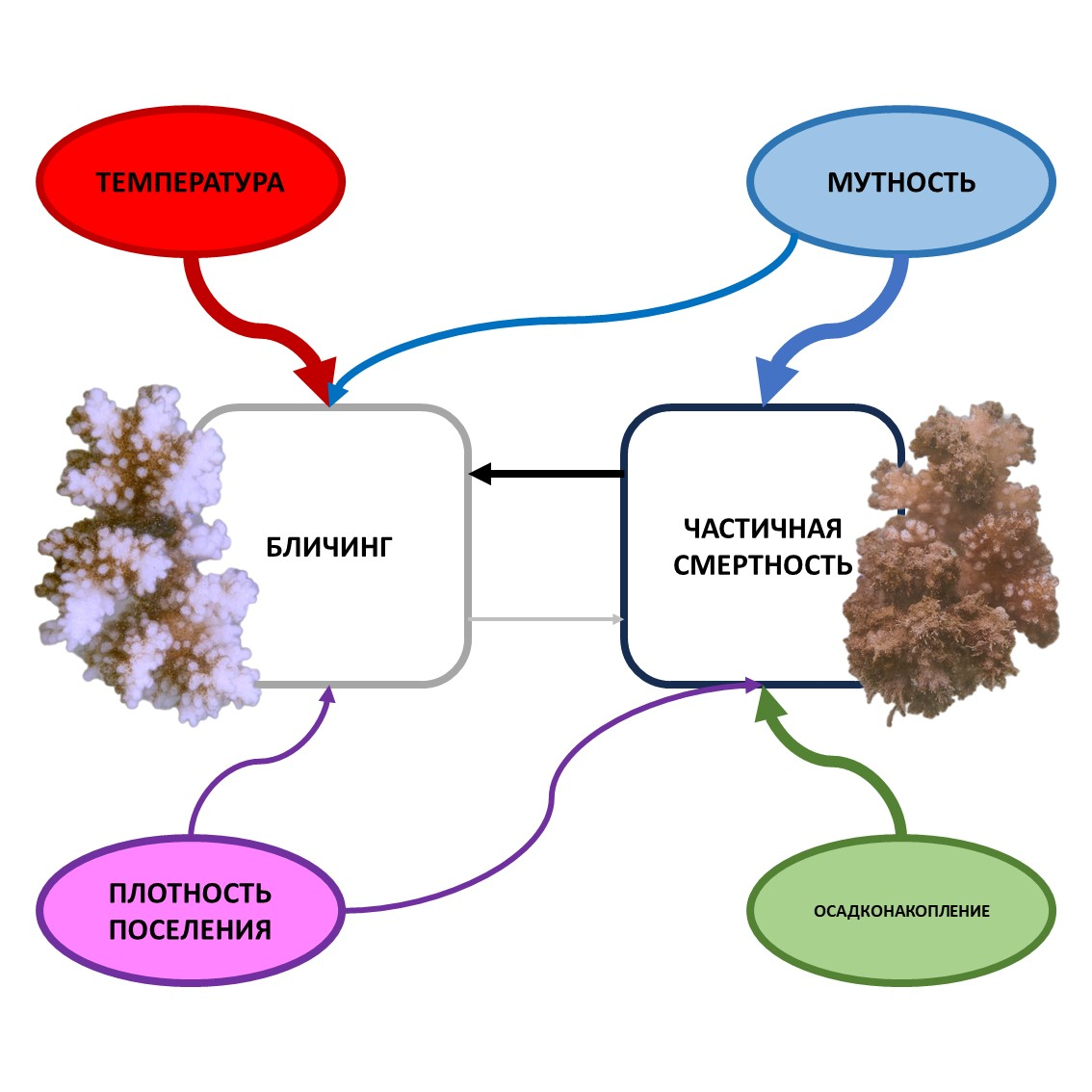

The work showed that the development of seasonal bleaching is driven (Figure 2) primarily by rising water temperatures, with colonies already suffering from partial mortality being more susceptible to bleaching than those without affected areas.

In turn, some of the mortality was caused by storms. Coral colonies suffering from bleaching were more likely to develop partial mortality than healthy ones. However, the effect of bleaching on partial mortality was markedly lower than that of partial mortality on bleaching.

Finally, the question was answered - can seasonal bleaching and partial mortality cause the death of corals?

According to observations, all dead colonies suffered from partial mortality before death. As expected, the lesion gradually spread throughout the coral, capturing more and more of it every day, which ultimately led to the death of the colony (Fig. 3). On the other hand, no direct relationship was found between seasonal bleaching and mortality. Yes, a number of colonies suffered from bleaching before their death, but this was more of an external manifestation of the deterioration of the coral’s condition, and not the cause of death.

Thus, the hypothesis was confirmed that the mass death of corals could be caused by their damage and overgrowth by macroalgae. On the other hand, the effect of seasonal bleaching on coral mortality was significantly weaker than expected. Both processes studied are caused by environmental factors (increased water temperature in the case of seasonal bleaching and storms in the case of partial mortality) and are related to each other (Fig. 4). The data obtained not only significantly expands knowledge about the biology of corals, but can also serve as a fundamental basis for the development of programs for the restoration of coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific.

This study was carried out within the framework of the Ecolan E - 3.1 program, task 1 Structure and dynamics of the formation of symbiotic communities associated with corals. In addition, the work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation grant No. 22-24-00836.

The results of the study are presented in more detail in the article Seasonal bleaching and partial mortality of Pocillopora verrucosa corals of the coast of central Vietnam, available at the link.