In a recent study, specialists from Russia and Spain for the first time studied the nutritional characteristics of representatives of two families of primitive fossil artiodactyls — anthracotheriums and entelodonts. The material for the study was the teeth of ungulates from the Quercy locality (southern France) and had been kept in the collections of the V.I. Vernadsky Geological Museum for more than a century. The age of the studied fossils corresponds to the Oligocene era (33.9-23 million years ago).

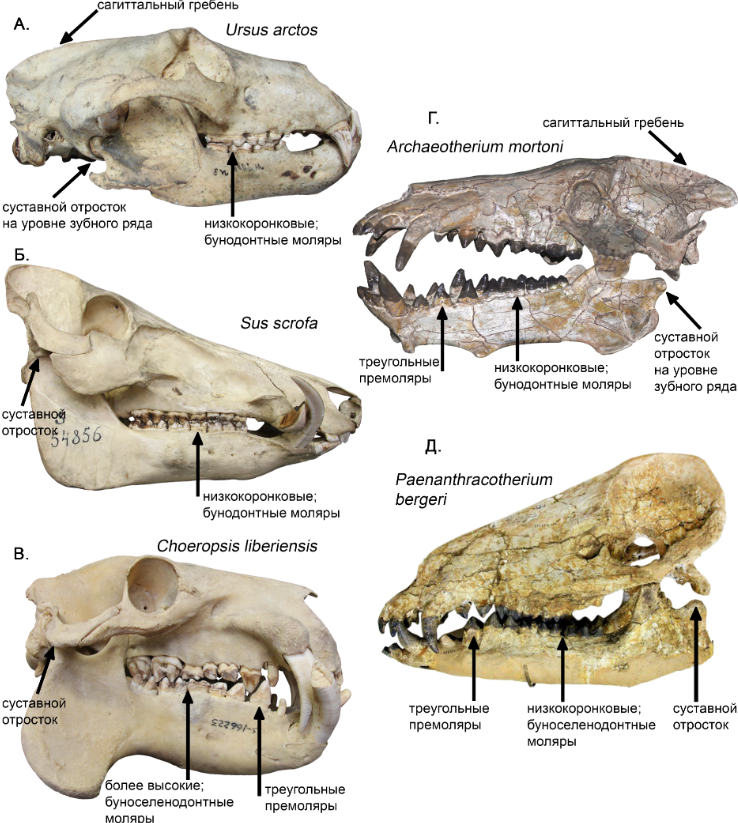

Representatives of the entelodontidae family are known in popular culture as “hell pigs”. They were characterized by impressive sizes, the largest representatives of the family reached the size of a bull, and a large skull up to 90 cm in length. There were numerous bony outgrowths and tubercles on the skull and lower jaw of entelodonts. These ungulates retained a full set of teeth characteristic of primitive placental mammals (three incisors, a canine, four premolars and three molars in each half of the upper and lower jaw), their incisors and canines were very large, the premolars were triangular in side view, the molars the teeth were quite small, low-crowned, and bunodont (i.e., tuberculate; Fig. 1). The skull and lower jaw of entelodonts had a number of features characteristic of carnivores: a powerful sagittal crest, large temporal fenestrae for masticatory muscles, the position of the articular tubercle on the lower jaw at the level of the dentition, and triangular premolar teeth when viewed from the side. The presence of these features formed the basis for reconstructions of entelodonts as scavengers, capable of chewing bones like hyenas, or even active predators.

Anthracotheriidae are a family of large pig-like mammals that lived in North Africa, Eurasia, and North and Central America from the late Eocene to the Miocene. Modern research shows that it is from the African branch of Anthracotherium that modern hippopotamuses originate, which are thus recent representatives of the family. The appearance of these animals had similar features to both pigs and hippos. These were medium-sized and large-sized ungulates with very short legs, their front limb was five-toed, the back was four-toed, and the lateral toes were well developed. Anthracotheriums had a large head with a long and narrow facial part of the skull and a full set of teeth. Their incisors were large and similar to the incisors of pigs (Fig. 1). The cheek teeth were low-crowned and often bunodont, but in some advanced species they became larger, almost square when viewed on the chewing surface, and selenodont (that is, having crescent-shaped cutting enamel ridges).

To study in detail the feeding habits of fossil ungulates, researchers used the method of analyzing microwear of tooth enamel. For a comparative analysis, 10 categories of animals were identified among modern ungulates and carnivores, occupying different ecological niches and specializing in a variety of food sources. These are (1) omnivores (pig, wild boar and brown bear), (2) specialized meat eaters (cheetah and lion), (3) meat-eating and bone-crunching (hyenas), (4) predators with a wide variety of food (fox), ( 5) mixed carnivory/fruitivory (common genet and palm civet), (6) piscivorous (otter), (7) folivorous (elk, giraffe, etc.), (8) frugivorous/folivorous (various duikers), (9) herbivorous (buffalo, zebra, etc.), (10) herbivores/semi-aquatic (common hippopotamus).

As a result of the analysis of the microwear pattern of the cheek teeth, it was shown that the large European Entelodon magnus was an omnivorous mammal, and the wear pattern of the enamel of its teeth was almost identical to the modern wild boar (Sus scrofa) and somewhat different from the brown bear (Ursus arctos). The diet of modern pigs is extremely diverse and varies greatly depending on the habitat and season of the year. Modern pigs feed on fresh green grasses, succulents, legumes, fruits, acorns, seeds, roots, bulbs, bark, fungi, invertebrates (worms, molluscs, beetles), fish, frogs, reptiles, small birds, rodents, newborn or injured mammals, and corpses, as well as eggs of birds and reptiles nesting on the ground. Microwear of tooth enamel indicates that similar plasticity in nutrition was characteristic of “hell pigs”.

Unlike entelodons, the studied anthracotheriums turned out to be specialized herbivores. Half of the studied individuals of the genus Anthracotherium were characterized by a folivorous diet, a quarter were folivorous + frugivorous, and another quarter were herbivorous. This dietary diversity could be due to seasonal variations in nutrition.

The data obtained as a result of the study allowed the authors to make assumptions about the nature of digestion in representatives of the two studied families of ancient and primitive pig-like artiodactyls. It is likely that entelodonts, with their simply constructed, pressing, tuberculate teeth and omnivorous diet, were characterized by the digestion of food in a simple stomach, just as it occurs in modern pigs. The deviation from omnivory towards leaf-and herbivory of Huanthracotheriums corresponds to the increased (compared to pigs and entelodonts) complexity of the structure of the chewing surface of their molars, on which cutting enamel ridges appear. It is likely that representatives of the genus Anthracotherium were characterized by cellulose fermentation in a complex stomach, just like modern hippopotamuses descended from Anthracotherium.

Source: Florent Rivals, RuslanI.Belyaev, VeraB.Basova, NatalyaE.Prilepskaya. Hogs, hippos or bears? Paleodiet of European Oligocene anthracotheres and entelodonts// Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 2023. V.611, 111363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.111363.