The epidemiological significance of ticks of the genus Argas has been known since 1897, since this genus includes at least 61 species of ticks that parasitize birds and bats, and is capable of being the host and carrier of a number of bacterial diseases, such as salmonellosis and agyptianellosis. The study presents the results of monitoring A. persicus mites collected from several bird species over 4 years in the Republic of Kalmykia, Russia. The study's findings suggest that domestic and wild birds can harbor large numbers of ticks, and their close proximity increases the likelihood of tick exchange. Scientists have found that a variety of non-migratory birds come into contact with poultry during the nesting season and are likely to exchange mites with them. It is clear from the study that despite regular acaricide treatment of farms, the presence of mites was extremely high, with the exception of small sporadic reductions.

It can be concluded that due to contacts between wild and domestic birds on private farms, acaricide treatments show low effectiveness, since Argas persicus mites move from wild birds to domestic birds.

The published article is devoted to the results of monitoring the infestation of birds with the mite Argas persicus (Oken, 1818). Ticks were collected from private farms in the village of Priyutnoye, Priyutnensky district, Republic of Kalmykia (Russia) from 2012 to 2016 as part of a project for continuous monitoring of bird ectoparasites

Ticks of the genus Argas Latreille (1796) are found in areas with temperate and warm climates; only a few species live in areas that sporadically reach 50 ℃ in the forest-steppe zone from the northern hemisphere. This genus includes at least 61 species of ticks that parasitize birds and bats and are capable of transmitting a number of bacterial diseases, such as salmonellosis and agyptianellosis. A. persicus is a carrier of spirochetosis, rickettsia, several other bacteria and hemoparasites in wild and domestic birds. Sometimes A. persicus even attacks humans, causing painful bites and invading their homes. The tick parasitizes chickens and other birds, feeding on blood at night and hiding in the cracks of buildings during the day. High numbers of A. persicus often lead to the death of birds both from large blood loss and from infectious diseases transmitted by ticks. The Persian tick may further increase its initial widespread distribution due to current global temperature changes, given that its optimal development temperature is 28–30℃ at 65–70% relative humidity with a lower temperature limit of 20℃.

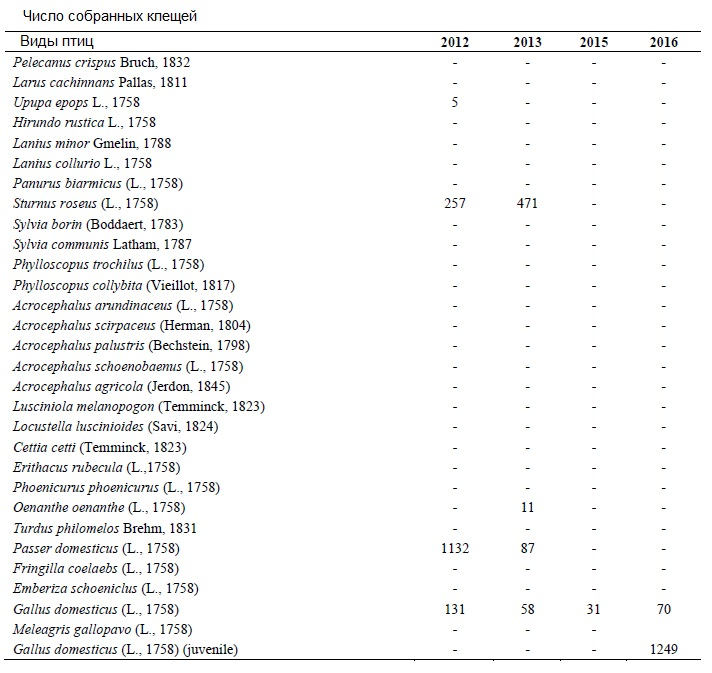

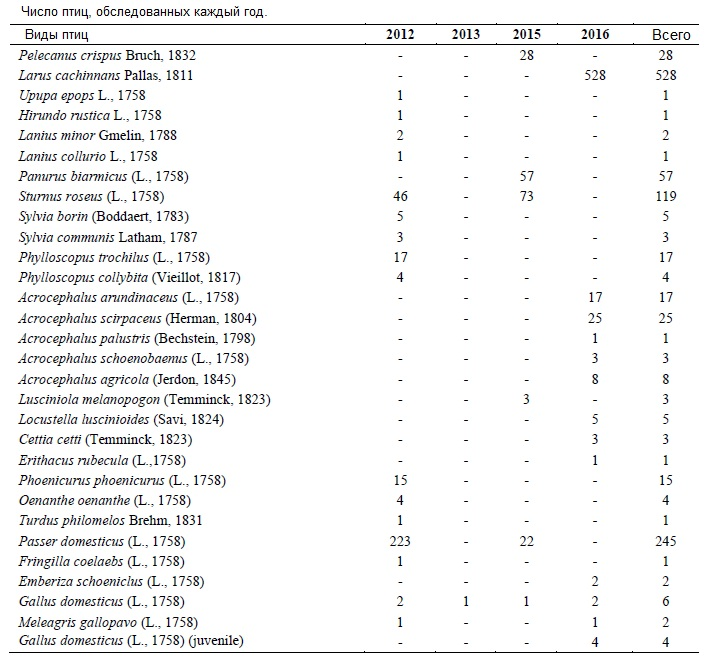

During the monitoring, 1242 bird species of two domestic and 27 wild species were examined. We found 290 adult ticks on poultry and 1963 adult ticks on wild birds.

Our results show that despite regular acaricide treatments on farms, mite presence was extremely high, with the exception of small temporary declines in mite numbers. A large number of mite larvae were observed on the chickens, which were likely attached to them from the soil of the farm. We confirmed that mites are actively colonizing cracks in the walls of buildings. We found that various birds from non-migratory species (Passer domesticus; Streptopelia decaocto (Frivaldszky, 1838); Columba livia L., 1758), long-distance species (Upupa epops; Hirundo rustica; Lanius minor; Oenanthe oenanthe) and nomadic species (Sturnus roseus) actively nest on farms. All of them come into contact with poultry during the nesting period. Among wild bird species, the highest tick load was observed in the synanthropic species Sturnus roseus and Passer domesticus L., 1758, which can act as reservoirs and vectors of ticks between wild bird populations and human buildings. Thus, domestic and wild birds may harbor large numbers of mites, and their close proximity increases the likelihood of mite exchange.

High densities of poultry on farms may facilitate the local spread of disease through ticks as disease vectors, and in turn ticks may be transported by wild birds to other regions during natural migrations.

https://doi.org/10.22073/pja.v12i2.77948