The form of the gallop that the animal uses determines the range of motion at the lumbosacral joint. There are two ways to increase your running speed: increase the frequency or length of your strides. In both cases, artiodactyls are capable of reaching an impressive top speed of 70-90 km/h.

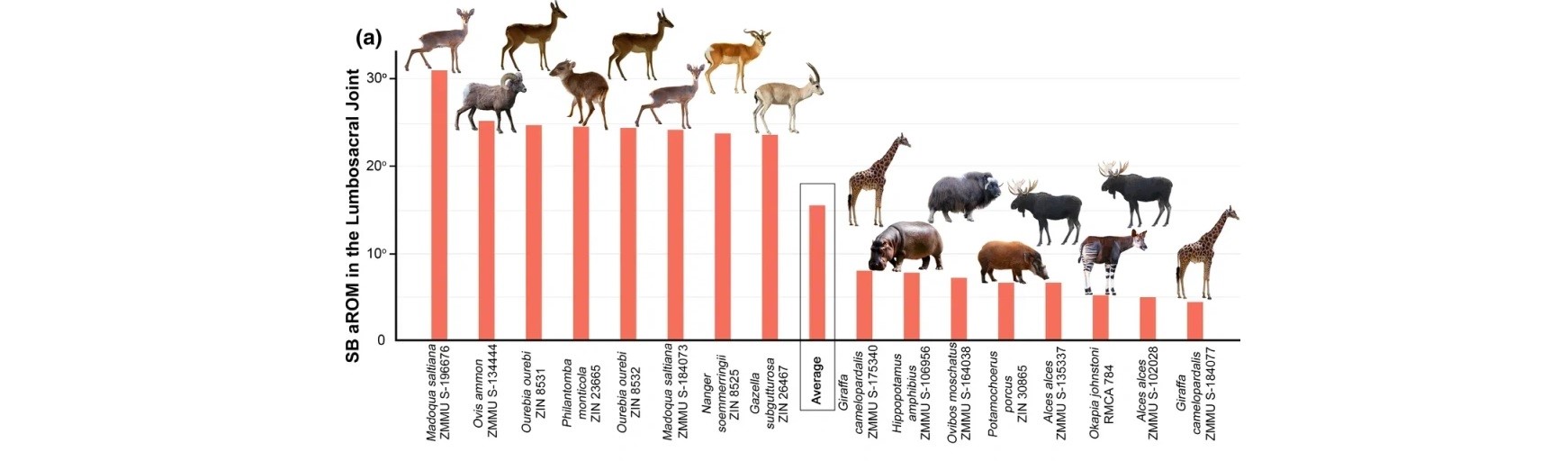

According to zoologists, mobility in the lumbosacral joint differs significantly in ungulates of the same size class, depending on the form of the canter used. In species adapted to the hopping-speed form of running, mobility in the lumbosacral joint is on average one and a half times higher than in species adapted to the speed form.

Thus, a more amplitude hopping-speed form of running demands from ungulates not only increased mobility in the limb joints compared to the high-speed form, but also higher mobility of the lower back and lumbosacral joint. Joint extension of the limbs and lower back allows species adapted to this form of running to cover a distance of up to 10 meters for each jump.

Scientists also found that the largest ungulates are characterized by a decrease in joint mobility throughout the spine. This also applies to the lumbosacral joint. Interestingly, its amplitude in large ungulates practically does not differ from the amplitude in the joints of the lumbar proper. Thus, its mobility is reduced more than in other joints. Scientists have suggested that the special role of the lumbosacral joint, which it plays in the use of jumping gaits by ungulates, is completely lost with an increase in size and transition to other forms of canter.

With an extreme increase in size, ungulates may completely refuse to gallop, as hippos do, which use trotting as their main ground gait, or even lose the ability to move without constant support on the ground, as happens with elephants.

The work was carried out with the support of the Russian Science Foundation. The results are published in the Journal of Anatomy.

In the photo: Artiodactyls with the most mobile and least mobile lumbosacral joint in the sagittal plane