During the years of depression in the rodent population, colonies of Mongolian gerbils look lifeless, since the animals almost never appear on the surface, and their alarm cries cannot be heard by humans, since they are emitted in the ultrasonic range, significantly exceeding the upper threshold of human hearing sensitivity.

Researchers from Lomonosov Moscow State University, the Institute of Natural Resources of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Moscow Zoo, and the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences studied the acoustic structure of ultrasonic alarm calls of Mongolian gerbils Meriones unguiculatus. The studies were conducted in the natural conditions of the Daurian Steppe. To verify the obtained recordings, the acoustic parameters of the ultrasounds of wild gerbils were compared with alarm calls recorded in family groups of Mongolian gerbils in captivity during simulated cage cleaning. In mid-summer 2021, when the data for this study were collected, the population density of the Mongolian gerbil and all other common rodent species in the Daurian Steppe was very low due to heavy snowfall in May, which flooded the burrows with breeding animals. As a result, in June and July there were many freshly dug burrows that looked inhabited, but live gerbils were seen only three times during 17 days of constant visits to the colonies.

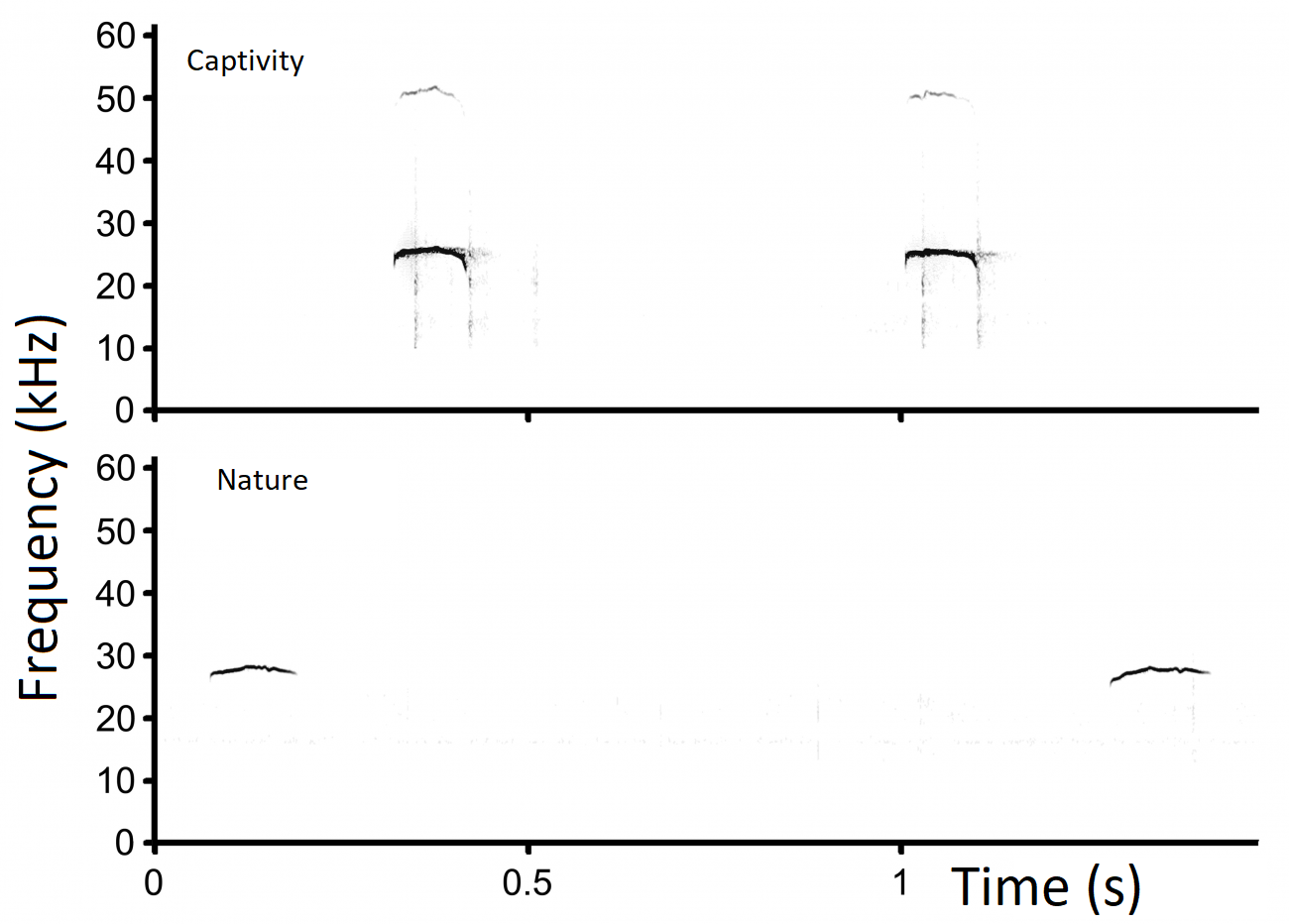

The ultrasonic calls were monitored using an Echo Meter Touch 2 PRO smartphone attachment, recording range from 6 kHz to 128 kHz. This attachment allows viewing the ultrasound spectrogram in real time. However, such a spectrogram is clearly visible when recording bat calls at night, and is not visible in the bright sun during the day, when Mongolian gerbils are active. Therefore, the recording was done blindly and then the recorded ultrasounds were immediately viewed on a computer. Two researchers regularly visited potentially inhabited gerbil colonies and conducted one recording session of 10-30 min per visit. The researcher stood or slowly moved along the entrances to the burrows, directing the recorder at the burrow openings.

All ultrasonic alarm calls were recorded from burrows; animals on the surface did not emit any calls. The presence of species-specific ultrasounds indicated that the burrow was inhabited on the day of recording. This approach can be used to search for inhabited burrows of Mongolian gerbils in conditions of severe population depression, when visual observations are ineffective.

In both the wild and captive conditions, the ultrasonic alarm calls of Mongolian gerbils were drawn-out ultrasounds with an average duration of 118 milliseconds, a flat fundamental frequency contour, and an average maximum fundamental frequency of 26.84 kHz. It was found that alarm calls of Mongolian gerbils in captivity were somewhat shorter and higher in fundamental frequency, and followed each other with shortened intervals between calls compared to wild conditions.

In addition to Mongolian gerbils, ultrasonic alarm calls are known only for three rodent species: the brown rat Rattus norvegicus, the Richardson's ground squirrel Spermophilus richardsonii, and the spotted ground squirrel S. suslicus. Mongolian gerbils also accompany their ultrasonic alarm calls with podophony: rhythmic paw strikes on the substrate in the frequency range audible to humans. However, podophony has only been observed and recorded in captivity. The evolutionary origin and adaptive use of the ultrasonic alarm call, which has poor penetrating ability both in burrows and above the soil surface, in a fairly large rodent remains unclear.

The results of the study were published in the Q1 journal Mammalian Biology: Volodin I.A., Klenova A.V., Kirilyuk V.E., Ilchenko O.G., Volodina E.V., 2024. Ultrasonic alarm call of Mongolian gerbils (Meriones ungiuculatus) in the wild and in captivity: a potential tool for detecting inhabited colonies during population depression. Mammalian Biology, v. 104, p. 407-416.