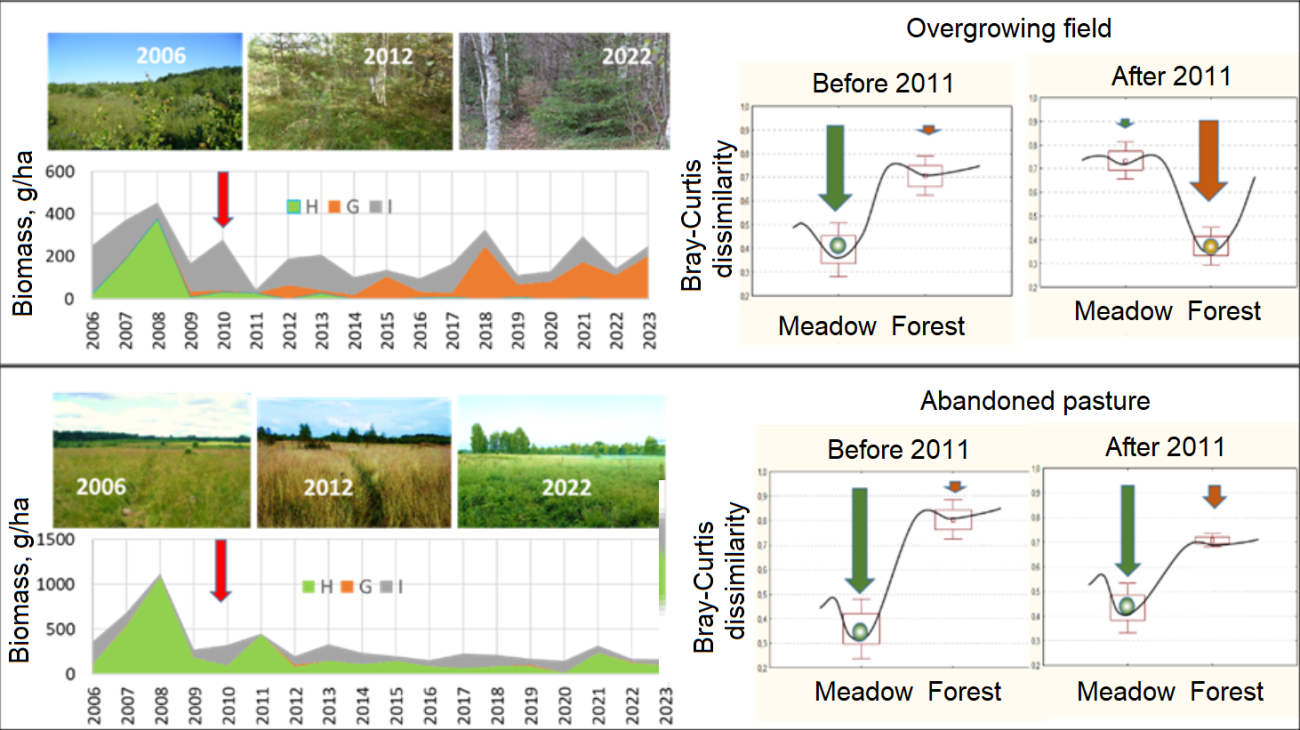

Fig. 1. On the left, biomass dynamics: H – herbivores; G – granivores; I – insectivores; the red arrow indicates the year of extreme drought. On the right, the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity with meadow and forest biomass patterns obtained from long-term observations in forest and open habitats.

Human well-being depends on the functioning of natural ecosystems, which provide us with everything from clean air and fertile soil to abundant timber. Ecosystems function by distributing matter and energy flows and are supported by the diversity of their constituent biological species. To preserve and restore these systems, scientists strive to predict their response to various environmental changes. The main difficulty is that ecosystems often change abruptly rather than gradually, changing their status after a certain "threshold." Understanding the nature of the "threshold effect" is a key component of modern ecological research. Scientists describe it using the "ball-in-hole" model. The greater the "depth of the hole," the greater the ecosystem's resilience. When impacted, the ecosystem - the ball - rolls back down. When the hole narrows, or when impacted very strongly, the ball pops out of the hole and takes a new position. Species that perform specific functions exert pressure on the ecological landscape: the greater the strength of the matter and energy flows associated with them, the greater the hole's depth. Ecosystem changes with a “threshold effect” have been studied spatially; direct observations of the emergence of a threshold over time are rare.

Scientists from the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEE RAS) observed this threshold effect during a 19-year study (2006-2025) in the Staritsky District of the Tver Region. They studied small mammal communities (rodents and shrews)—indicators of ecosystem health. The feeding habits of different small mammal species are well known, and knowing their population density (number of individuals per hectare) and their weight allows one to determine the "depth of the hole" formed by species associated with a given ecosystem.

The study was conducted on two adjacent sites with different histories: a former pasture that retained the features of a natural meadow, and an abandoned cropland where vegetation rapidly transitioned from a mixed-grass meadow to a young forest. The extreme drought of 2010 ultimately led to different results. In the stable meadow (former pasture), the animal community remained unchanged, but the overall species biomass decreased. However, in the overgrown cropland, the same drought triggered a threshold transformation: the meadow system abruptly transitioned to a forest-like structure.

Why were the responses so different? The meadow on the cropland had not yet had time to form as an ecosystem; its "hole" was shallow. A severe drought easily overcame this threshold and transformed the ecosystem into a new state. In contrast, in the pastured meadow—an ecosystem that had been developing over many decades—the "hole" was much deeper, and the ecosystem resisted the same impact. Thus, this study demonstrates for the first time, using a specific example, how the same climate event can lead either to temporary changes in an established ecosystem or to a complete restructuring of communities in an unstructured system, i.e., one still in the process of formation.