Current methods for assessing stress in animals rely primarily on data collected from males of model rodent species. This is because females are often excluded from studies, as their physiological parameters are considered more variable. However, to accurately assess the well-being of wild populations of small mammals, stress levels in both sexes must be taken into account. To further explore sex differences in adaptation to stress, scientists from the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEE RAS) studied the response to prolonged, unpredictable stress in wild-type house mice (Mus musculus musculus). These animals, unlike laboratory strains, are not yet genetically adapted to captivity and may respond to stress differently.

The mice were exposed to a variety of moderate stressors (1-hour immobilization, 12-hour wet bedding, 1-hour cold at 4°C, 1-hour predator urine odor, etc.) for five weeks, and their performance was then compared with that of a control group. This approach prevented habituation to the stressor, which occurs with repeated exposure to the same stimulus, and also limited the overall intensity of the adverse effects.

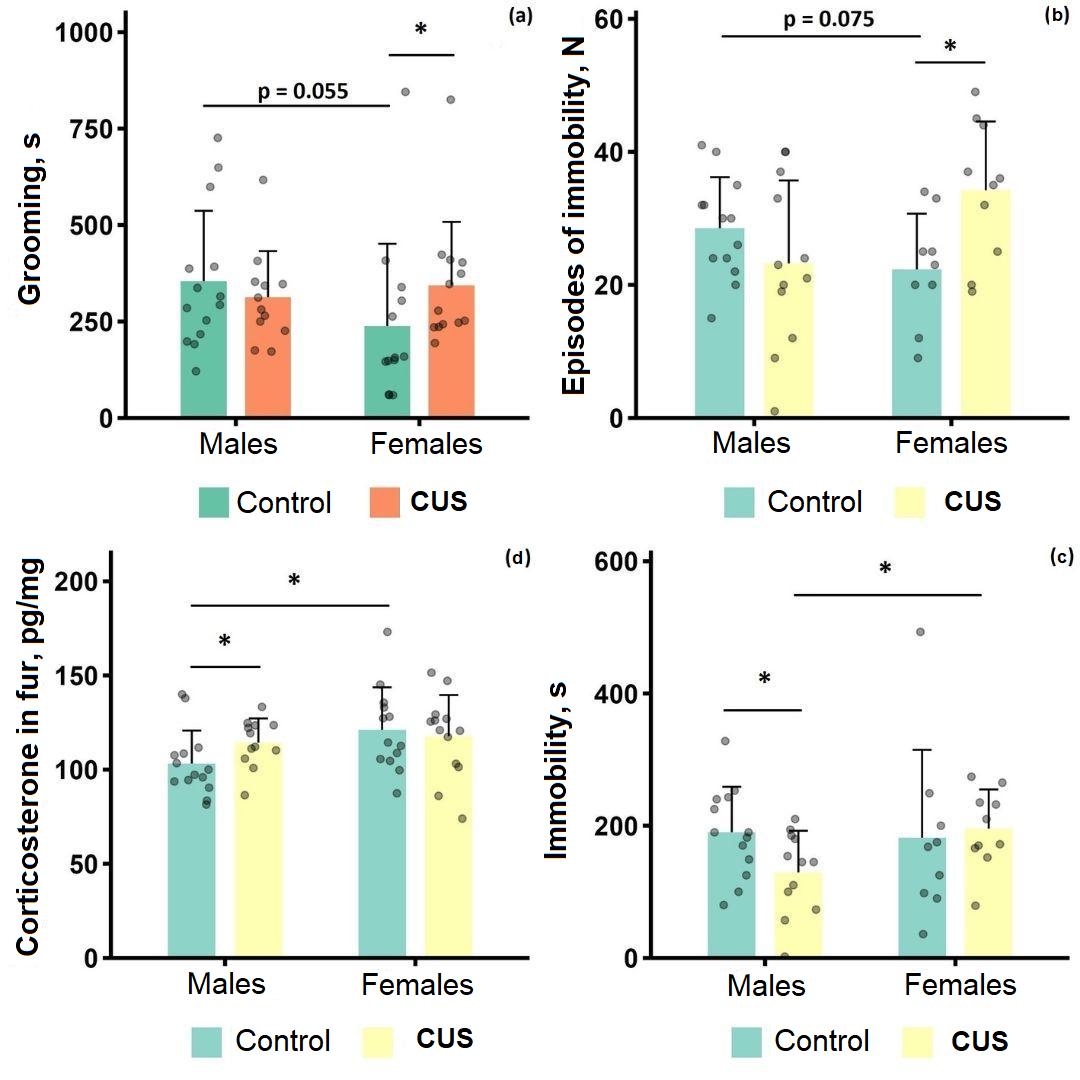

Figure 1. The effect of chronic unpredictable stress on behavior in two behavioral tests (a, b, c) and fur corticosterone levels (d). Control – control group of mice. CUS – group of mice exposed to chronic unpredictable stress for five weeks. Grooming duration was determined in the open field test, and the total duration and number of immobility episodes (i.e., periods of complete inactivity) were determined in the tail suspension test.

The pattern of body weight changes depended on gender: weight gain in stressed females was less than in controls, while no such differences were observed in males. Changes in the weight of organs directly involved in the stress response were also recorded in mice. Behavioral responses under chronic stress also differed by gender. Long-term stressed females were more likely to exhibit behavioral signs of an internal conflict between the desire to explore new things and risk avoidance. Conversely, males, after similar stressful exposures, became more active in the same situation (Fig. 1 a, b, c). Furthermore, higher levels of the stress hormone corticosterone were recorded in the fur of males (Fig. 1 d).

"The choice of fur for analysis was not accidental. Fur accumulates stress hormones (glucocorticoids) over weeks or even months, making glucocorticoid levels in fur a more reliable indicator of chronic stress than a single blood hormone measurement," said Tatyana Laktionova, a junior researcher at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Overall, our observations of morphophysiological and behavioral changes suggest that, under identical experimental conditions, female house mice of natural origin are more vulnerable to chronic stress than males. This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation grant 23-24-00414 (supervised by Senior Researcher V.V. Voznesenskaya).

The results of the study were published in the journal Biology (Q1).

Related materials:

Science.Mail: "Scientists have discovered that mouse stress depends on gender"