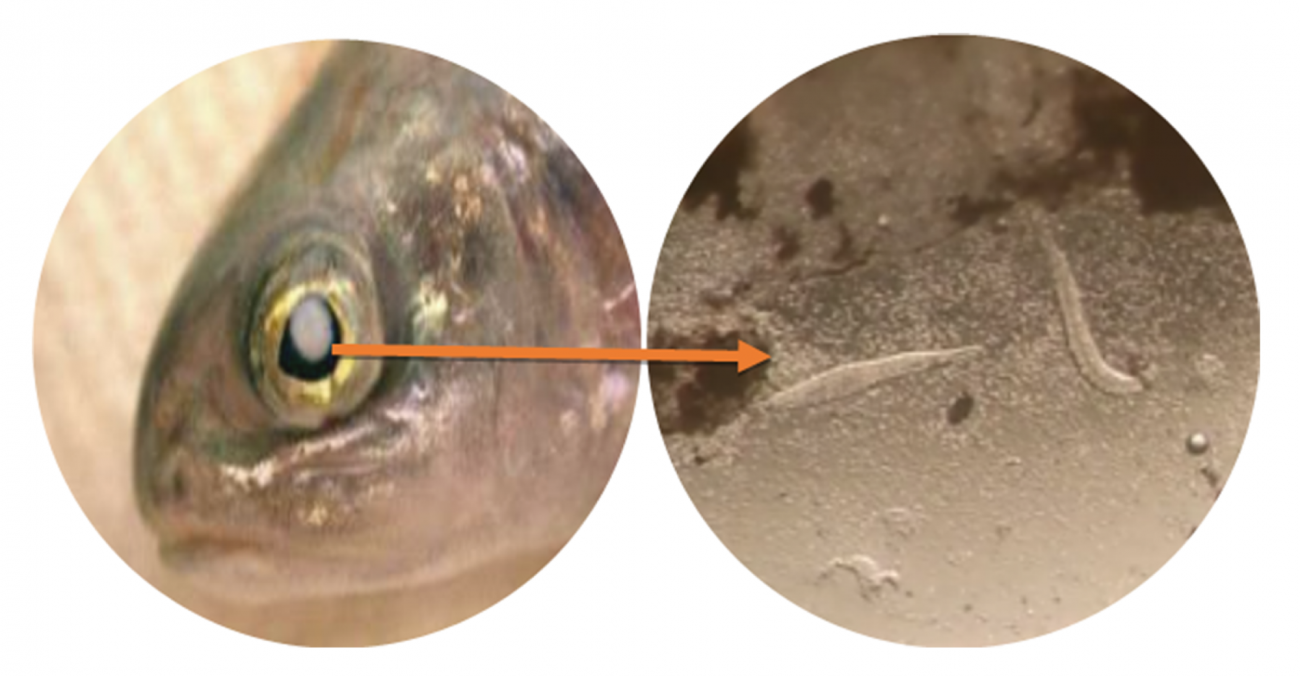

Many parasites are able to change the behavior of their hosts to their advantage. This evolutionary adaptation is called "parasitic manipulation." In recent decades, this phenomenon has attracted increasing attention from researchers. There have been so many examples of manipulation that many parasites are unreasonably classified as manipulators without proper experimental testing. This happened with the trematode Tylodelphys clavata, which parasitizes the eyes of fish. Its close relative (from the same Diplostomidae family), the trematode Diplostomum pseudospathaceum, is indeed a parasite-manipulator, weakening the defensive behavior of fish. Perhaps this is why it was previously believed that T. clavata also changes the behavior of its hosts. It was assumed that during the day T. clavata moves to the front of the eye closer to the pupil, blocking the light and blinding the fish, thereby causing behavioral changes. In the dark, the parasite goes deep into the eye, where it feeds.

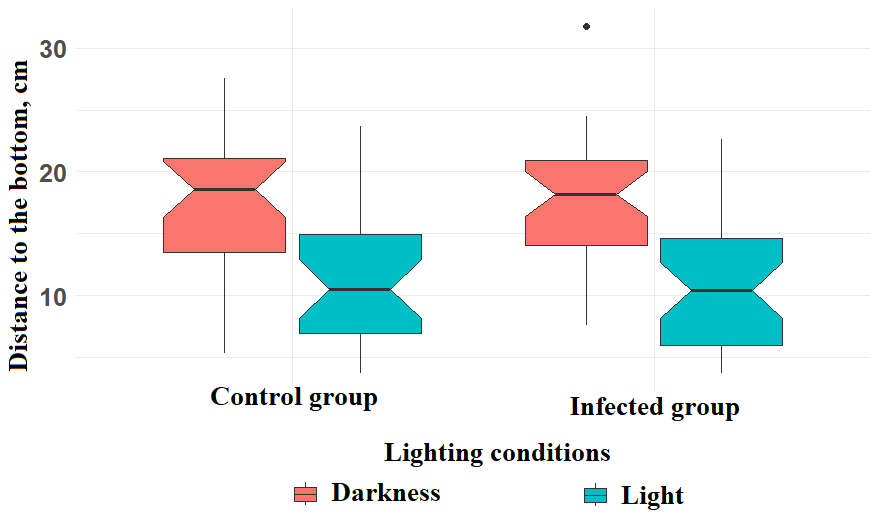

Scientists from the Laboratory of Lower Vertebrate Behavior and the Center for Parasitology at the Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEE RAS) experimentally tested whether the behavior of Dolly Varden infected with T. clavata changes. The fish were infected under controlled laboratory conditions, and the experimental design was identical to that for D. pseudospathaceum (a manipulator parasite; Gopko et al., 2023). Taking into account the putative mechanism of manipulation, the scientists tested the fish in the light and in the dark. Three behavioral traits of the fish were tested: locomotor activity, preferred diving depth, and the ability to avoid a net (imitation of a predator attack).

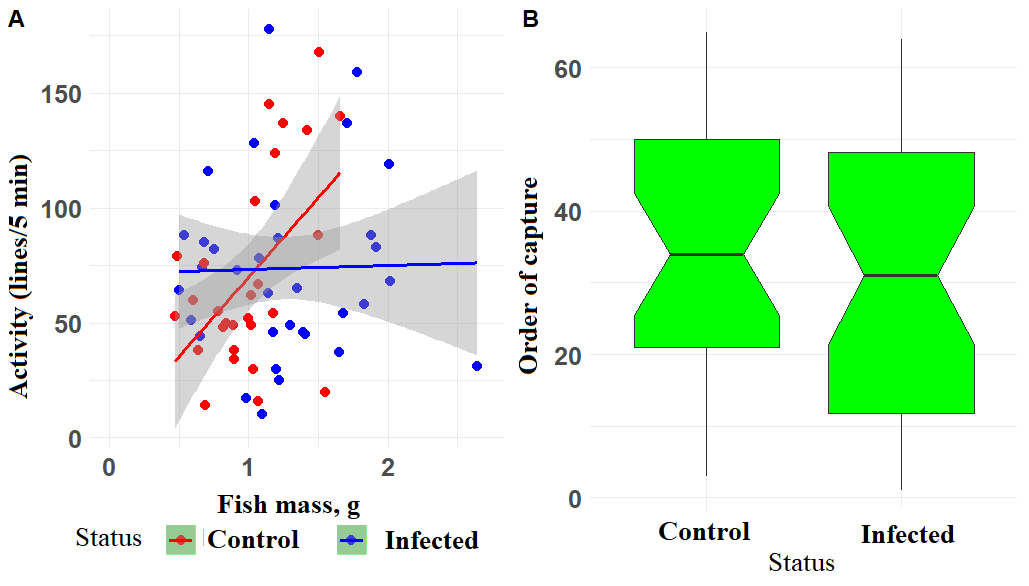

None of these behavioral traits were found to be altered by the parasite (Figure 2), whereas D. pseudospathaceum has previously been shown to sabotage each of them.

The relationship between fish activity and size was found to differ among fish with different infection status (Figure 2A). Control fish increased their activity with increasing body weight, while infected fish did not.

The obtained data show how much parasites can differ in their ability to manipulate host behavior, even if they are phylogenetically close and occupy similar ecological niches. The results cast doubt on the previously speculative assumption about the ability of T. clavata to change fish behavior.

The work was carried out within the framework of the RSF project No. 23-24-00419 and published in the first quartile journal: Gopko, M., Sotnikov, D., Savina, K., Molchanov, A., Mironova, E. (2024). Does phylogenetic relatedness imply similar manipulative ability in parasites?. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 143(4), blae101.

A preprint of the publication can be found on the authors' page in Researchgate.