In an article by Institute employee Alexei Tsessarsky, published this year in the Journal of Anatomy, a hypothesis is proposed to explain the mechanism for the emergence of the unusual structure of the jaw apparatus and the head of sturgeons in general.

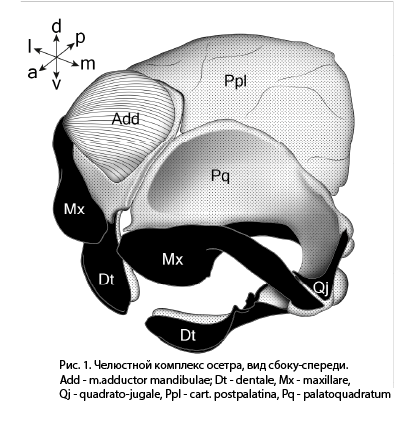

Unlike all other ray-finned fish, and bony fish in general, in sturgeons, the upper jaw does not articulate with the front of the skull, but instead, the branches of the upper jaw are turned inward with their anterior ends and close with each other, forming the so-called maxillary symphysis (Fig. 1).

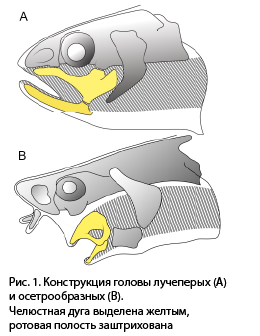

The maxillary symphysis is considered a key synapomorphy of sturgeons, distinguishing them from other actinopterygians, but this is only half the story. If in all “normal” fish the ventral side of the anterior part of the skull serves as a skeletal support for the roof of the oral cavity (Fig. 2A), then in sturgeons this entire section is located in front of the mouth and is in no way connected with the oral cavity (Fig. 2B).

Thus, the design of the head of sturgeons is a striking example of a deep evolutionary transformation (novelty), which we would like to explain in terms of phylogeny and evolution. However, this is far from a trivial task, since even the most basal Mesozoic representatives of the group show the same general jaw pattern as modern sturgeons, which makes the transition from the putative ancestral (paleoniscoid) pattern to the state characteristic of sturgeons completely incomprehensible.

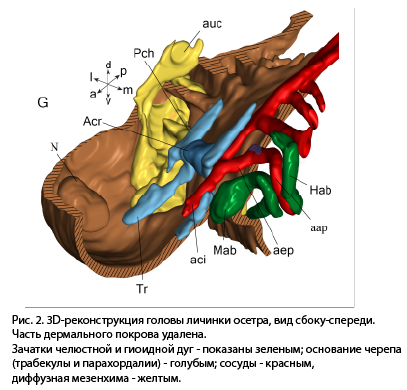

For more than 150 years, since the times of Karl Gegenbauer and Thomas Huxley, in all textbooks and reports on the morphology of vertebrates, special sections have been devoted to sturgeons and their close relatives, polyodontids, but no explanation has been offered for the unusual design of the head of these fish. Paradoxically, the sturgeon skull is a classic and, at the same time, completely mysterious object in the comparative anatomy of vertebrates. The solution to this riddle was made possible by analysis of the earliest stages of head development, when the skeletal components are still represented by barely formed mesenchymal accumulations. For this purpose, the method of constructing 3D models from serial histological sections was used (Fig. 3).

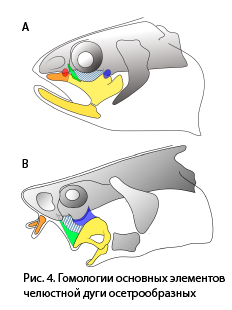

A thorough analysis of the development of the jaw arch of sturgeons made it possible to establish well-founded homologies of the components of the upper jaw and, in particular, to show that the anterior ends of the branches of the upper jaw, which in other fish articulate with the axial skull, in sturgeons separated from the jaw arch and turned into supporting cartilages of specialized sensory organ - antennae (Fig. 4).

This process was most likely triggered by paedomorphic underdevelopment of the lower jaw in the ancestors of sturgeons, which led to exposure of the anterior part of the palate and opened the possibility for the transformation of this area into an organ of taste and tactile sensitivity. The remaining parts of the maxilla rotated medially and restored occlusion with a shortened mandible. This is how the maxillary symphysis was formed. The article was published in the Journal of Anatomy: Alexey Tsessarsky, What is missing from the sturgeon jaw: Developmental morphology of the upper jaw in Acipenser, Journal of Anatomy. 2023; 00:1–21, DOI: 10.1111/joa.13953