Since 2007, a large international project to reintroduce (restore) the population of a once widespread cat species, the Persian leopard (also known as the Caucasian or Anatolian leopard), has been underway in the North Caucasus.

The project was developed by the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences and approved by the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation in 2007. IEE RAS is its leading scientific organization.

Scientists from the Institute of Mountain Ecology of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEMT RAS) are participating in the project. The project was also supported by the A.K. Tembotov Institute of Ecology and Geography of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEGT RAS), the Caspian Institute of Biological Resources of the Dagestan Federal Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, zoologists from the Moscow Zoo, the Caucasus and North Ossetian Nature Reserves, the Alania and Elbrus National Parks, staff of the Caucasian Leopard Recovery Center at Sochi National Park, with the assistance of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA), and several other organizations. The Russian federal project is part of an international effort to restore this subspecies throughout its range.

Unfortunately, funding for the project has effectively ceased; international organizations have withdrawn, as has RusHydro, which supported the work in the Central Caucasus from 2017 to 2023. Anna Yachmennikova, a senior researcher at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences and a candidate of biological sciences, spoke to Poisk about what has been achieved over the years, what hasn't, and what the future holds.

- Anna, how many cats have been released into the wild since the project began, and how many continue to live in the wild in the regions where they were released?

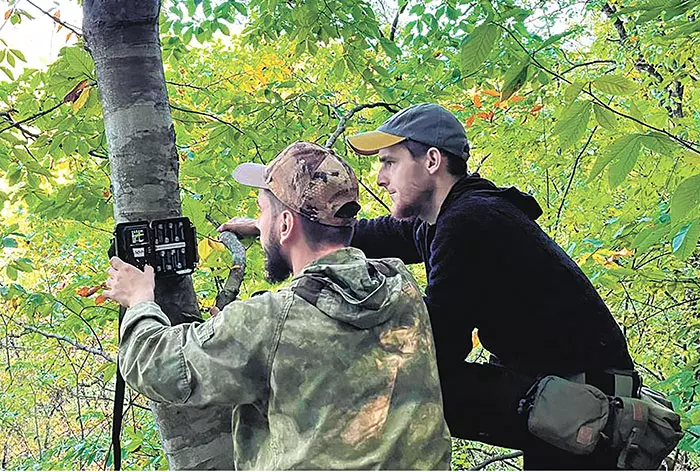

- I can give a precise figure for the first part of the question: fifteen. Seven leopards (four males and three females) were released in the Western Caucasus, and eight animals (four males and four females) in the Central Caucasus. I can't answer the second question with certainty, as we currently lack the necessary standard monitoring equipment for the area covered. We have a small number of camera traps from our partners at the Institute of Mountain Ecology in Kabardino-Balkaria, and there are camera traps purchased for North Ossetia-Alania in 2017-2018. The Caspian Institute of Biological Resources in Dagestan also installed a few cameras, but all of this is completely insufficient to obtain an objective picture. The special collars that all the animals were equipped with upon release have expired, the batteries are exhausted, and the collars themselves have come loose on many animals. There are no new collars available.

Persian leopards are occasionally spotted here and there, but we can't confirm whether they're ours unless we receive a photo. Each released animal has a "spot passport." Leopards enter the North Caucasus from Azerbaijan, Georgia, and South Ossetia. Natural dispersal of young individuals from the core population remaining in Iran is underway.

They don't travel to our region often, but such sightings are nevertheless recorded almost annually. Sometimes cats are captured on camera traps, and then we can confirm that they are indeed our released predators from the Sochi center (by comparing the trap photos with the photos in the "passports").

There is currently no complete and reliable information regarding the presence of cubs in the wild.

– How many animals are needed for the population to become stable and begin to develop relatively sustainably?

– According to our estimates, there should be at least 50 breeding Persian leopards in the North Caucasus. The regular birth and survival of cubs are crucial components of development; without them, any population will sooner or later disappear.

– So such a large number of animals no longer exist today. Why was it necessary to develop and adopt the project at all? Since the disappearance of leopards in the North Caucasus, the biota has been occupied by other fauna, including predators, and the region's relatively small territory has been significantly transformed by human activity.

– The Caucasus Mountains ecoregion, due to its remarkable biodiversity, is incredibly stable. All the components that existed 100 years ago are present here, except for the leopard—the key regulator of food chains and stabilizer of ecosystems. The global scientific community believes it is necessary to revive species that have been extinct for no more than 100 years to restore ecosystem health. The last Persian leopard was killed in the North Caucasus in the 1950s. The timeframe is appropriate." Reviving such a large predator, and for the first time in history, from scratch, is a major and exciting challenge from both a scientific and practical standpoint. When Academician Vyacheslav Vladimirovich Rozhnov, then Director of the Institute of Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences, presented this idea to Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, he received the president's enthusiastic support.

In 2009, the Sochi center was established, with the primary goal of breeding and preparing this species for release into the wild. The first two male leopards were brought from Turkmenistan. In April 2010, two females from Iran arrived, and in October 2012, a pair of leopards from the Lisbon Zoo. This marked the beginning of a very large and multifaceted project. Its success depends on many factors, one of the most important being the coherence and coordination of all components of the vast team. In essence, each part of the project is, in some way, an independent program.

As an example, I'll use the preparation of a predator for an encounter with a human. Each leopard undergoes this training while growing up at the center. Then, it takes its own "state exams". Here's one of them: What decision will a predator make if it encounters not a large, dangerous man with a gun, but a woman or a child? The testing involves several provocation stages: first, the subjects position themselves and move so that they face the direction from which the leopard might emerge (toward its enormous enclosure). The subjects are invisible. The next stage is more provocative: the subjects turn their backs to the predator. This would seem to be the ideal position for an attack. To prevent this from happening, in the wild, a leopard must be extremely reluctant to encounter a biped, regardless of its size or actions, and if it does encounter one, it must quickly increase the distance between itself and them. All these conditioned reflexes are implanted in the animal's consciousness by its handlers while it grows in the center. The animal is taught never to regard a human as "lunch or dinner.”

Our institute, in collaboration with colleagues from the Moscow Zoo, has developed numerous tests to assess the readiness of spotted predators for a free life. These are modified and refined based on the experience gained. However, controversial situations still arise from time to time. In one such case, one of the animals was diagnosed with hip rickets during development, and one hind leg sometimes malfunctioned. This called into question its ability to hunt large game as an adult. Experts doubted the advisability of its release, despite its good behavioral results, but the Ministry of Natural Resources decided otherwise. From its first days on its own, the leopard adopted a cautious lifestyle, avoiding chasing deer and wild boar, catching smaller animals, and, for the time being, adapting well. However, it did not survive its first winter (the most critical natural test of survival) – in December, we received a death signal from its collar. It's important to note the following: despite its physical limitations, the animal remained docile, never attempted to intrude on human habitation, and never hunted easy prey — cattle (it hunted jackals, badgers, raccoon dogs, foxes, etc.). In other words, its upbringing proved to be exceptionally sound.

– The first leopards were sent to "conquer the unknown” in the Caucasus Nature Reserve. Then the location of the release changed, dropping a few animals in North Ossetia-Alania in a small range of specially protected areas. Why?

– The Kharkiv Shaposhnikov Caucasian State Nature Biosphere Reserve is the oldest (established in 1924 - Ed.) and largest protected area in the North Caucasus. It would have been logical to begin the release there. But then a number of unaccounted factors came to light. The most important was that there were no historical traces of predators in this area. Leopards record these traces even decades after their relatives have disappeared. This helps the new inhabitants adapt. While exploring a new territory, they suddenly stumble upon the spots where the spotted animals had previously roamed. "Aha," the cat thinks, "relatives lived here, so this must be a good place.”

We released our first predators into "deep space." Moreover, much of the preparation was done with a familiar forested habitat in mind, and the Caucasus Nature Reserve has many alpine and subalpine zones. Naturally, these were completely unfamiliar to the spotted ones. Another unaccounted for initial factor was the high population density of competing predators—bears and wolves. While the high density of ungulates seemed an undeniable advantage in the area, the sheer number of competitors was a significant disadvantage. A large ungulate must not only be hunted, but also consumed entirely to replenish the energy expended, meaning it must be able to preserve the food for several days. Few animals, for example, can consume a large deer in one sitting. The leopard catches it, eats it, and decides to rest, when suddenly a bear shows up uninvited. “Come on, share your dinner!" It's pure racketeering. It turns out the cat wasn't trained in self-defense. Having expended its energy and strength, it's forced to give up its "honestly earned" reward. Once or twice this happens, the leopard becomes "offended" and leaves the inhospitable land.

However, in North Ossetia-Alania, not only are historical traces of Persian leopards preserved, but fresh ones are regularly spotted. Both border guards and hydroelectric power station workers have repeatedly spotted the alien animals, filming them with video cameras and taking photos with camera traps. Psychological factors played a significant role in the selection of North Ossetia-Alania as the territory: the republic's coat of arms depicts the Persian leopard (also known as the Caucasian leopard), and residents welcomed the opportunity to have live predators in their native nature reserves. Environmental education, public outreach, and educational activities are among the most important subprograms of our work. For example, the difficulty of implementing it in Dagestan became one of the decisive reasons for the absence of Sochi animals here, although by most other parameters the conditions are excellent.

– Does the territory of the Chechen Republic meet all the requirements if, despite the termination of project funding, you've continued research there?

– The fact is that, together with the Berkut State Budgetary Institution of the Ministry of Natural Resources of North Ossetia-Alania, we received support from the Presidential Fund for Nature—a grant for the project, 'Guardian of the Mountains and Masters of the Forests—the Caucasian Leopard and Bison.' The project aims to create a modern wildlife monitoring system in the republic, including camera traps and other modern technology. The system will be implemented in the Turmonsky Nature Reserve, where, according to our information, released leopards live.

We also won a similar grant from the Presidential Foundation for the Chechen Republic as participants in a larger project to monitor biodiversity in Russian protected areas. Research initiated last year with support from the Nature and People Foundation showed that the area is suitable for leopard recovery. Incidentally, it is one of the project's target areas; it was simply not possible to begin systematic work there previously.

However, before drawing final conclusions, it is necessary to assess the potential habitat capacity of the animals throughout the Russian Caucasus and determine which areas are suitable for the successful existence of a certain number of individuals. A key part of the survey is studying the food supply of local ecosystems, i.e., assessing the abundance of the leopard's main prey species (ungulates and medium-sized carnivores), and the threats and risks to spotted leopards, specifically the population density of competitor species (large carnivores comparable to the leopard).

The creation of a standard monitoring model will enable continuous, non-invasive observation of the most mobile elements of ecosystems (animals) and the recording of new leopard incursions using camera traps.

In 2024, we began this work in the Shatoisky District, within the Sovetsky Federal Nature Reserve. This year, we are expanding and improving the quality of this work through our participation in the project "Formation of a National Photo Monitoring Network in Protected Areas of Russia."

– So, the project continues, but has now been fragmented into separate programs with independent funding?

– Absolutely. Of course, a unified program, unified funding, and unified coordination are more effective. Unfortunately, life makes its own adjustments, sometimes quite significant. Several projects to conserve rare animal and bird species are currently underway across the country: the Amur tiger, the Siberian crane... Different teams are doing what they know best and as best they can. Some crumbs, tiny seeds of their labor, sprout and take root, and nature takes them and returns the result. We hope that this Persian predator will eventually establish itself in the North Caucasus. Perhaps one of our spotted cats has already given birth to kittens; we just don't know it yet.

Related materials: