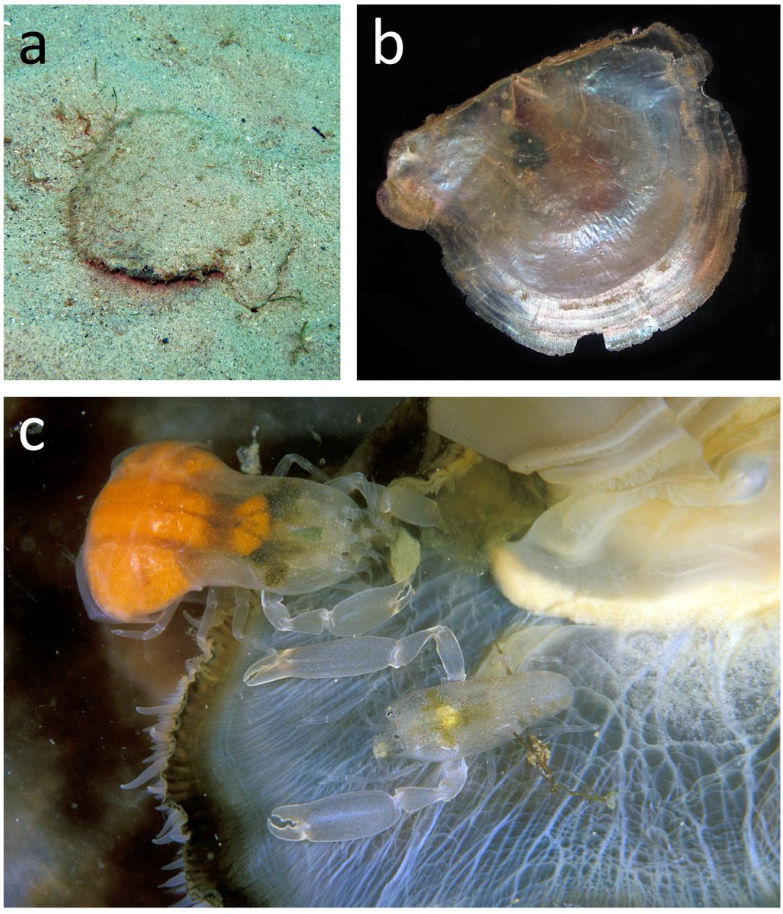

B - Saddle oyster Placuna ephippium in the laboratory after being cleared of debris.

C - Male (bottom) and female (top) symbiotic shrimp Chernocaris placunae

In marine ecosystems, many smaller invertebrates adopt a symbiotic lifestyle to avoid predation. Improving this strategy, many symbiotic species moved to living inside the body of their host, and also became monogrammed in order to more efficiently use this resource (= space inside the host). At the same time, social monogamy is preferable in species that live in relatively small and morphologically simple hosts.

Currently, in the context of global climate change and coastal ecosystems in the rapidly developing countries of Southeast Asia, many marine communities are undergoing significant changes. Do they affect the social behavior of marine species?

An international team of scientists from the USA (Clemson University, South Carolina) and Russia (IEE RAS) tested this hypothesis on the symbiotic shrimp Chernocaris placunae, which lives in the mantle cavity of the saddle oyster Placuna ephippium, widespread in the Indo-Western Pacific Ocean. The work was carried out in 2003-2004 in two locations with different environmental conditions in Nha Trang Bay, Vietnam, and published in the leading international journal Symbiosis.

According to the data obtained, the shrimp C. placunae live in the mantle cavity of their hosts in the form of heterosexual pairs more often than would be expected by pure chance. On Tre Island, there was a strong correlation between host and shrimp body size in both males and females, and shrimp mating was dependent on their body size; Moreover, the length of the shrimp carapace was positively correlated between males and females forming social pairs. Overall, these data suggest that C. placunae shrimp are socially and sexually monogamous on Tre (Che) Island. In turn, on Hon Mun island there was no correlation between the body size of the host and symbiotic shrimp, and mating of shrimp was not dependent on their body size, suggesting that C. placunae is socially, but not necessarily sexually, monogamous (and probably promiscuous), as this second section of the study has shown. Body size and host abundance were lower on Tre Island compared to Hon Mun Island, further suggesting that “refuge trait” (= host) drives, at least to some extent, the observed differences in the mating system of C. placunae shrimp.

When trying to identify the cause of this phenomenon, the researchers came to this conclusion. From the point of view of the general environmental situation in Nha Trang Bay, Tre Island is a highly polluted area, since there is a large city nearby and the removal of fresh water from a large river, while Hon Mun Island is located at a considerable distance from these polluting factors and is located in a more seaward part of the bay .

A comparison of these factors suggests that pollution may affect the mating system of the species studied in this work. Are similar changes occurring in the mating patterns of other marine organisms due to modern changes in the marine environment? This is a highly relevant topic that deserves further attention. Answering these questions requires manipulative ecological laboratory and perhaps natural experiments aimed at understanding how shifts in community components caused by global change and anthropogenic impacts influence and alter the social behavior of marine organisms.